CIRCLES OF LIGHT

Feminine Teshuva, Torat HaTzeva &

the Secret to Healing in Kislev

Rising in Kislev: Re-emergence of Hidden Light

in a Generation of Feminine Teshuva

By Rachel Leah Weiman

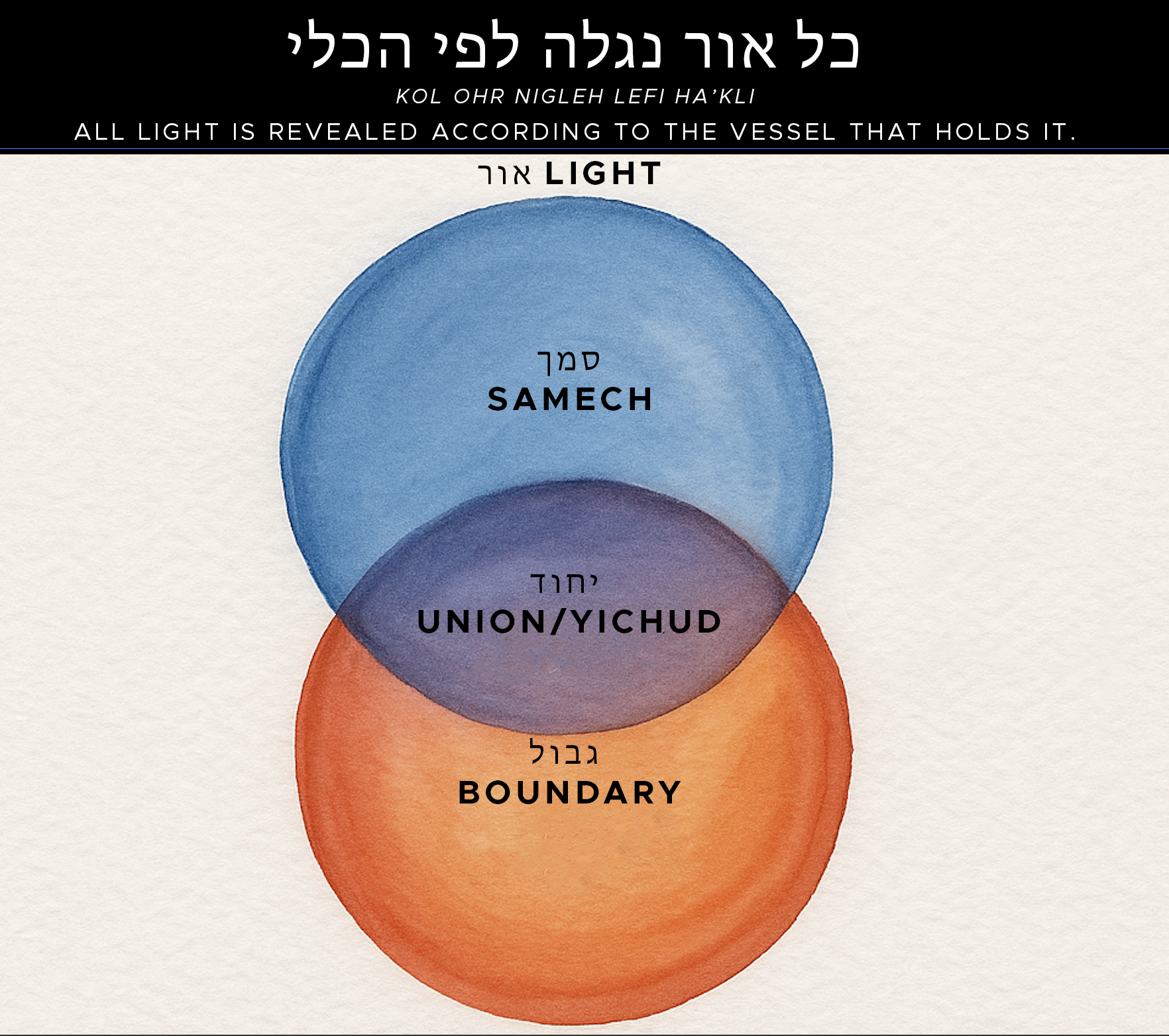

כָּל אוֹר נִגְלֶה לְפִי הַכְּלִי

“Kol ohr nigleh lefi ha’kli

All light is revealed according to its vessel.

— Zohar

הָאוֹר הַפָּשׁוּט מִתְפָּשֵׁט בְּכָל הַצְּדָדִים

Ha’ohr ha’pashut mispashet b’chol ha’tzdadim

The simple light spreads in every direction.

— Ramak, Pardes Rimonim

BS”D

This article explores the expansive convergence of feminine teshuva, Torat HaTzeva (the Torah of color), and the subtle, embodied healing pathways rising in the generation of Kislev. Rooted in classical Kabbalah, Chassidut, somatic wisdom, contemporary color theory, and the experiential depth of women’s workshops, it proposes that today’s creative Torah circles represent a collective return to the earliest layers of the soul — the layers formed in the womb, before language, where inner light was undivided and process was still sweet.

Drawing from Rav Kook’s teaching on חטאת הארץ הכמוסה — the hidden cosmic wound— and from the Torah of the Samech, the article shows how breath, movement, color, Torah, and circle form a unified vessel for restoring the sweetness of process, awakening compassion toward the self, healing generational imprints, and cultivating a lived geulah-consciousness, gathering the scattered “stones” of our neshamot souls and our collective body, Knesset Yisrael.

Through this lens, feminine teshuva — embodied, relational, rooted in softness and breath — is emerging through the surprising medium of Torat HaTzeva, the Torah of Color. In these circle-based art practices, participants touch what Rav Kook calls the hidden cosmic wound, rooted in Gan Eden, restoring the sweetness of becoming and reopening ancient pathways of healing, wholeness, and return.

The Circle as Daily Practice:

Living Inside the Light

When the workshop ends, the real work begins.

Circle becomes stance.

Breath becomes prayer.

Color becomes perception.

Softness becomes strength.

Living with geulah-consciousness means:

allowing process to be sweet,

trusting gestation,

honoring the pace of becoming,

creating yichud-spaces in relationships,

gathering rather than judging,

seeing fruit inside the tree,

recognizing that every person, even the difficult ones, are “stones in my field” waiting to be gathered.

This is how feminine teshuva transforms the world.

Not through force.

Not through ideology.

But through remembrance.

She does not conquer darkness. She gestates light.

She does not scatter. She gathers.

She does not rush. She reveals.

And as circles close, as breaths deepen,

as colors soften into one another —

a new architecture of geulah begins to emerge.

Quiet. Certain. Like Kislev. Like hidden light.

Like a circle that closes itself from within.

When Teshuva Appears

Teshuva is not an effort, not self-criticism, not the labor of fixing oneself. Teshuva is a light. When this light appears, the original desire for good — the soul’s innate nature — strengthens from within. Rav Kook describes this moment as the opening of a tzinnor (צִנּוֹר), a spiritual channel. Through that channel, joy begins to flow “מִנַּחַל עֵדֶנִים” — from a “stream of Eden.” This is his language for a very real spiritual experience: effortless joy, an innate delight that rises naturally, the soul drinking directly from its Source. And when a person’s practical mind and emotional faculties begin to absorb these new inner sensations, a new form of mussar emerges — not guilt-based, pressure-based discipline, but a mussar ha-tahor ha-elyon, a pure, elevated life-force that beautifies life and helps it succeed. It refines the person naturally, from the inside, without force — the way a flower opens when touched by the right light.

Torat HaTzeva begins

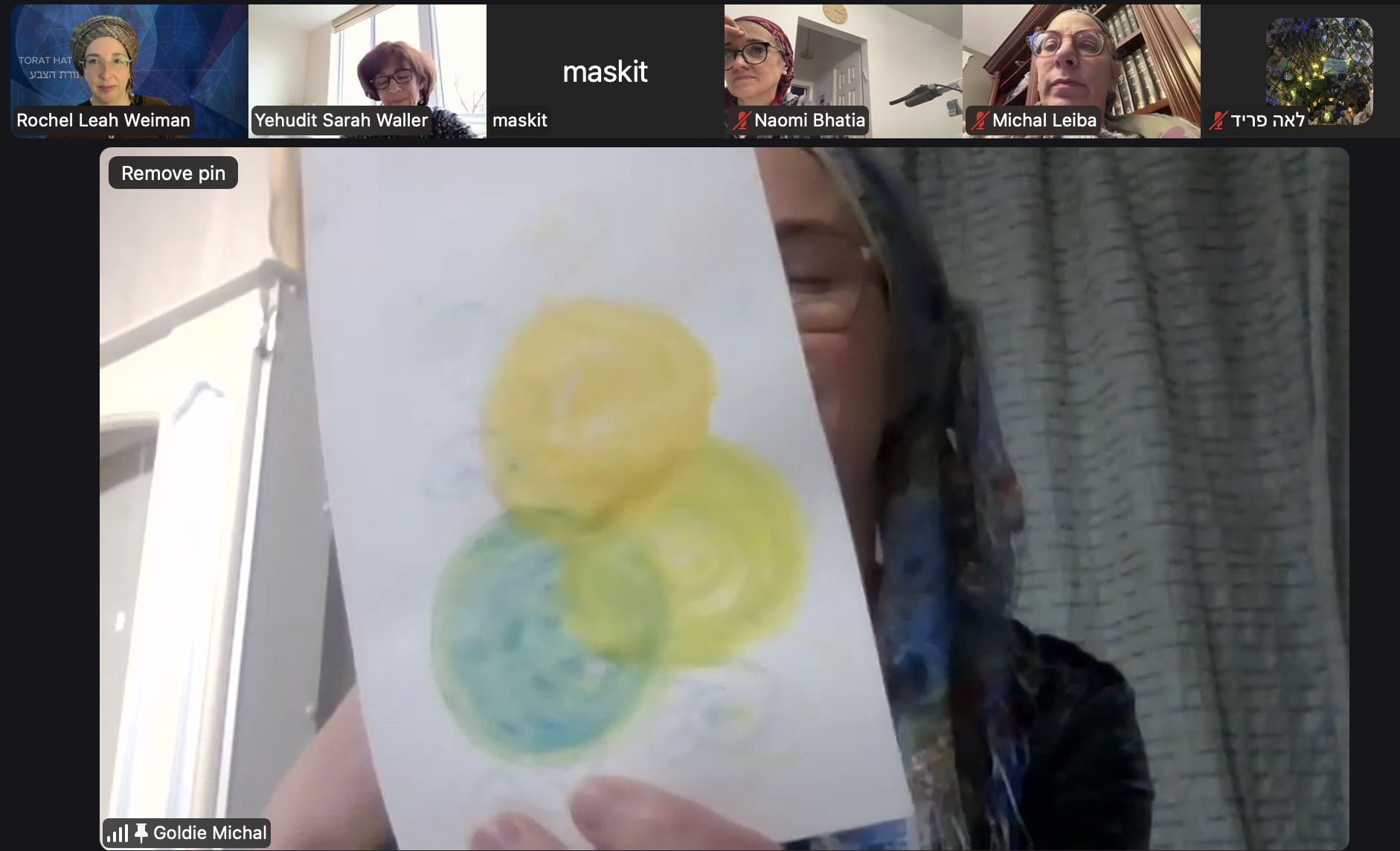

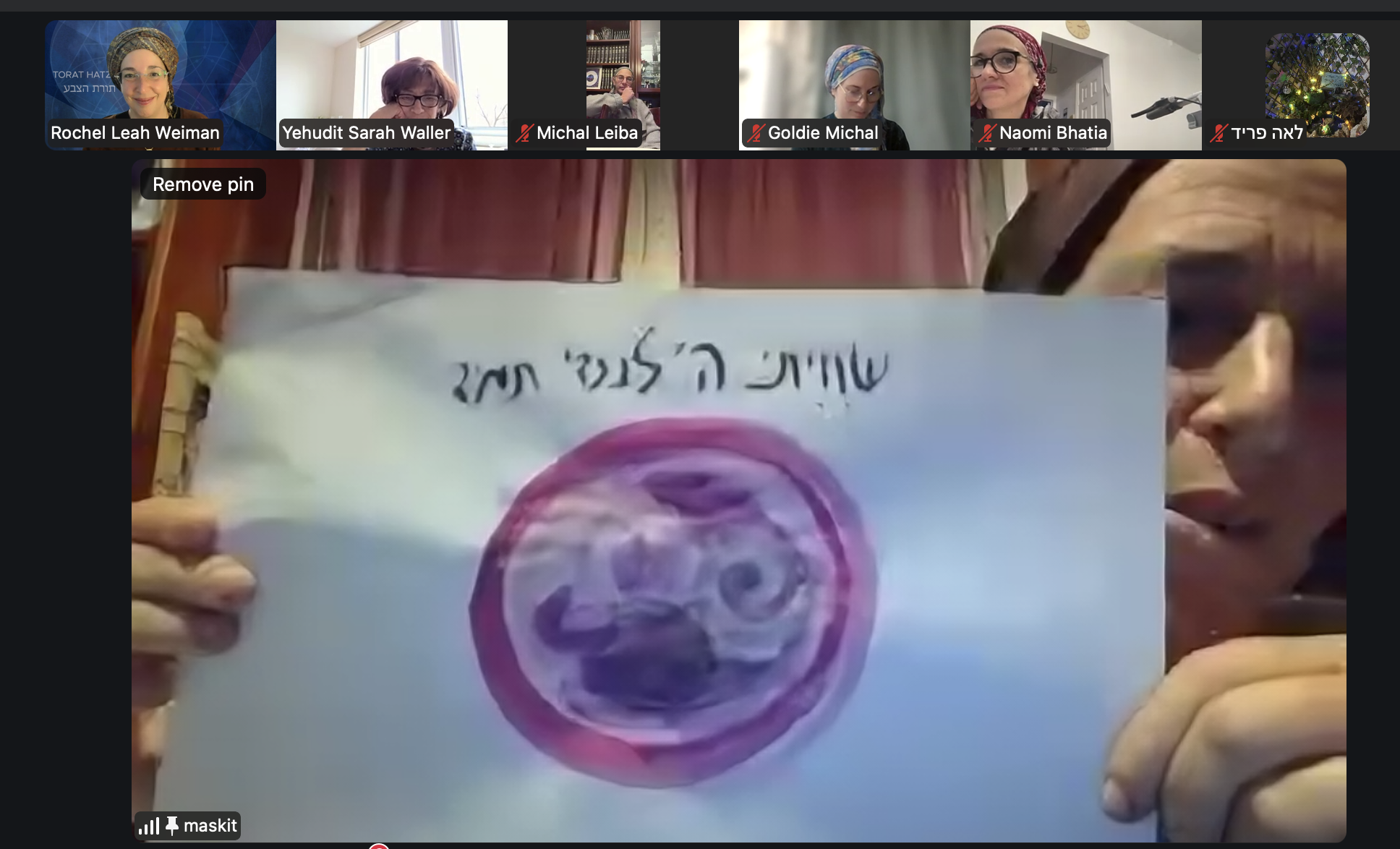

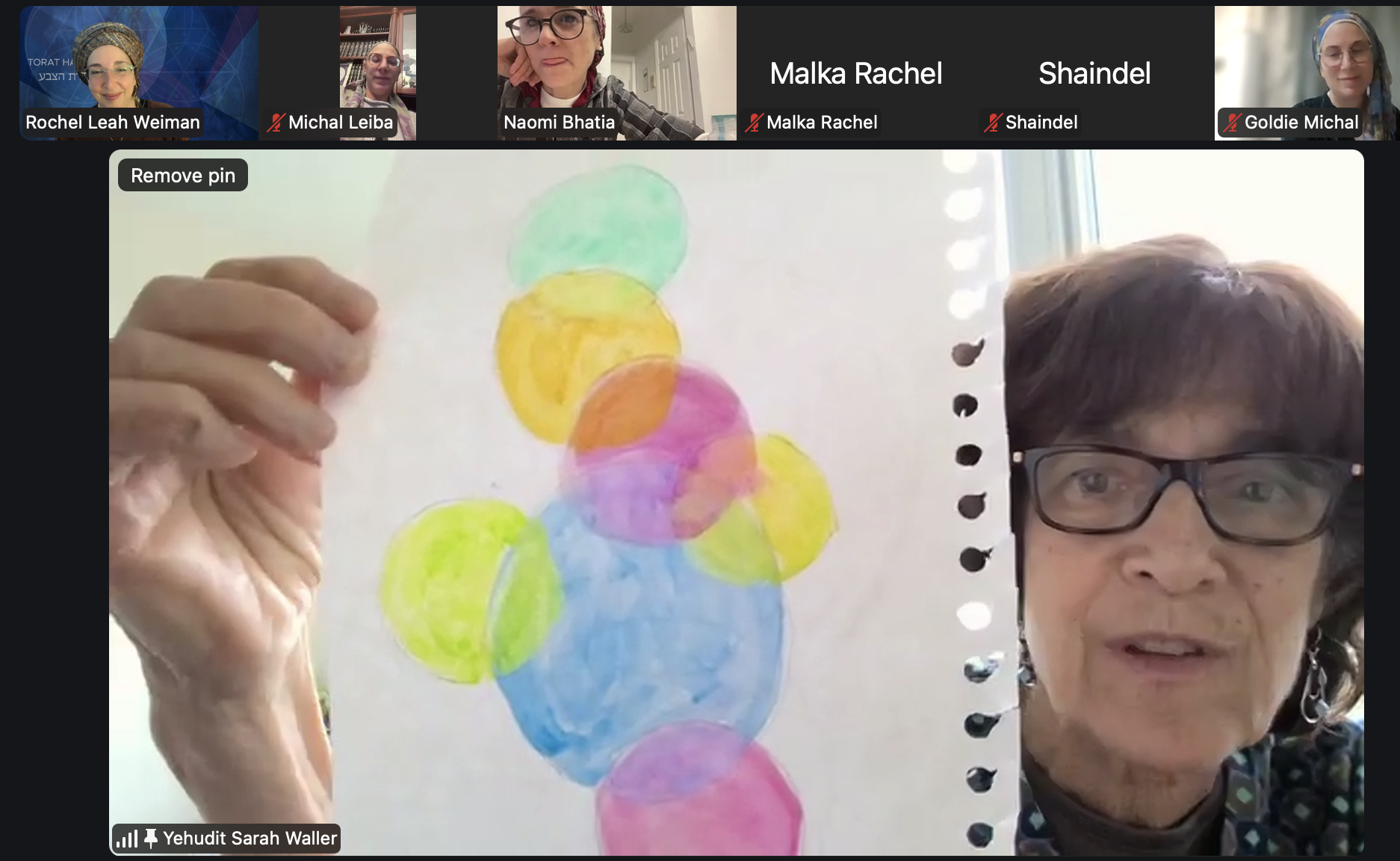

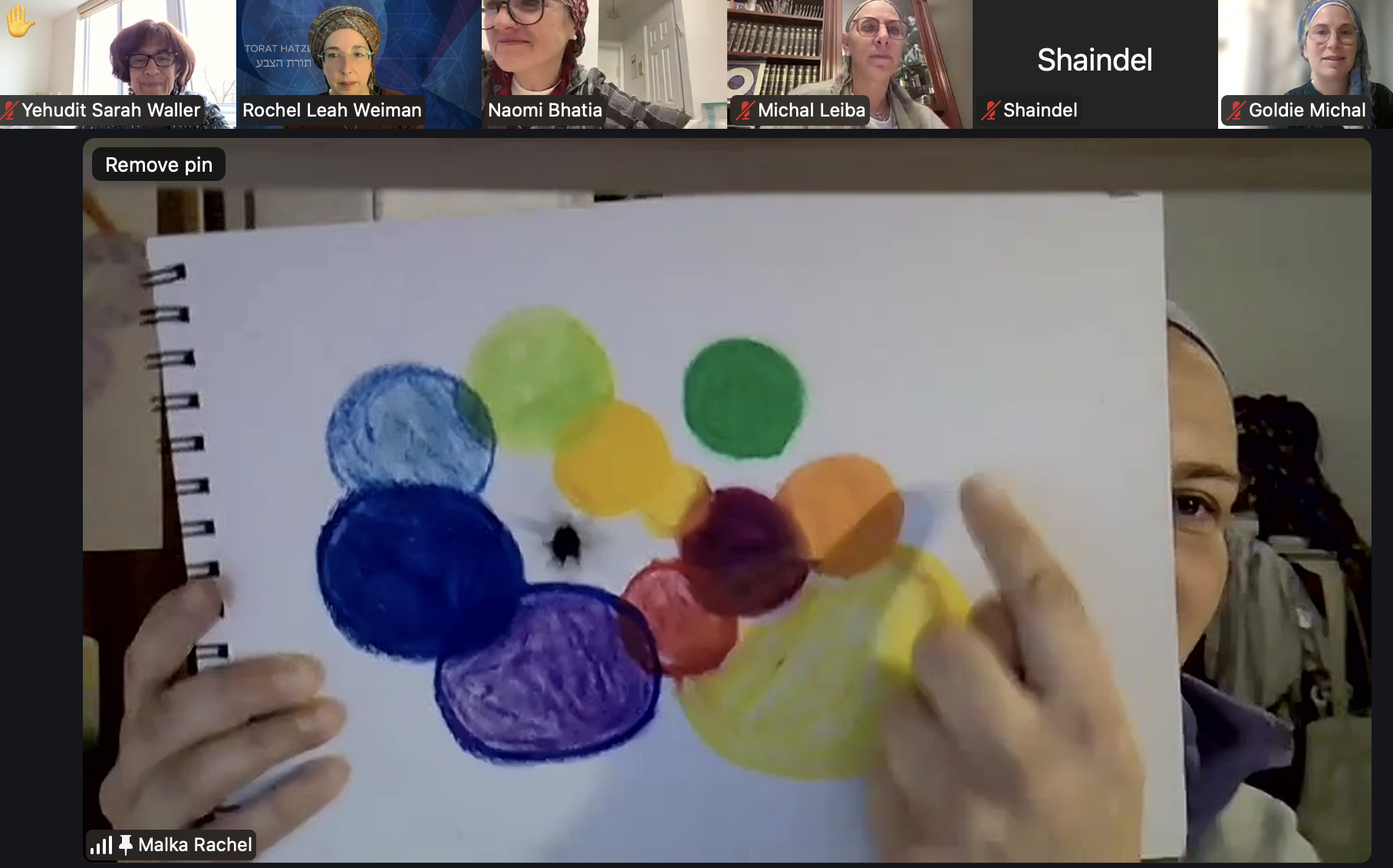

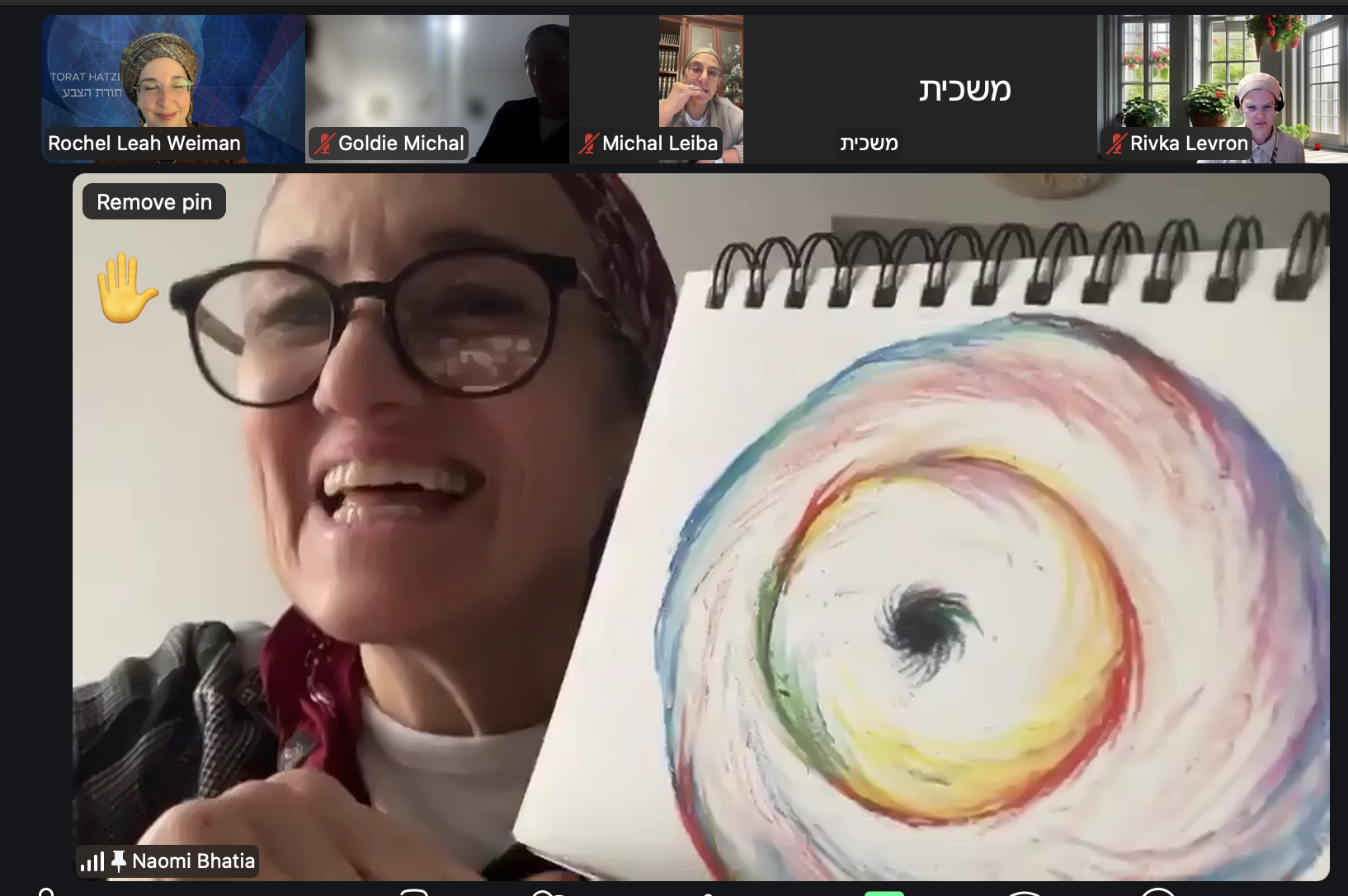

There are moments in history when something subtle begins to move beneath the surface. Not loudly, not dramatically, not with the force of a storm — but with the quiet persistence of dawn. A soft tremor rises inside the collective soul, a whisper of something ancient returning. In our generation, this movement is unmistakable. Something is happening among women — in homes, in studios, in late-night Zoom circles where faces glow softly from the light of a single lamp. Women are gathering not to perform, not to debate, not to impress — but to remember. To soften. To return.

In these circles, a new-old kind of teshuva is emerging: feminine, embodied, intuitive, tender, and deeply rooted in the earliest layers of the self. A teshuva that returns us not to ideology but to sensation. Not to dogma but to breath. Not to abstraction but to color. Not to the linear but to the circular — to the womb-like consciousness of Kislev and the letter ס, Samech, whose shape holds the secret of Divine support: “Somech Hashem l’chol ha’noflim.” Hashem supports all who fall.

This is where Torat HaTzeva begins: in the place before language, before separation, where light was still whole.

They come with paints, colored pencils, brushes, breath, silence. They come with longing and fatigue, with unspoken prayers, with the weight of this moment in Jewish history pressing against their ribs. And something happens in these spaces — something gentle, something radical — as if the deepest layers of the soul, the pre-verbal layers formed in the womb, finally have permission to breathe again.

This is where Torat HaTzeva begins: in the place before separation, before narrative, where light was whole — Ohr Pashut — and the world still remembered its original circle.

There are teachings that feel ancient the moment you hear them—not because they are old, but because they describe something the soul recognizes before the mind does. They name something the soul already knows. For me, that moment arrived with two short passages from Rav Kook’s Orot HaTeshuva (14:6–7). These teachings, written a century ago, feel of remarkable contemporary relevance, especially for the women of our generation. That is the point of departure for this article which Rav Kook articulates a spiritual anthropology of remarkable contemporary relevance.

Today, the teachings of the Arizal — once whispered in small circles of seekers — are re-emerging through women’s breath, women’s hands, women’s paintbrushes, women’s movement, women’s tears, women’s laughter, and women’s sacred gatherings.

The wisdom is no longer confined to books or theoretical study. It is being lived, expressed, embodied. It is arising in the body itself.

Across communities, something quiet and profound is happening: women are accessing ancient Kabbalistic light not through abstract meditation alone, but through sensory, creative, kinesthetic experience. Breath becomes a gateway. Color becomes a language. Movement becomes interpretation. Water, touch, vibration, sound — all become vessels for receiving and transmitting hidden Torah. The teachings flow into lived practice. In these spaces, the Arizal’s map of the soul is not an intellectual diagram but a felt reality. The inner world becomes visible. What was once abstract becomes intimate.

This return is not a departure from scholarship; it is its flowering. Texts illuminate the practice, and the practice illuminates the texts. Rav Kook wrote that the higher light seeks vessels that are prepared to receive it. What we see now is an entire generation of women becoming such vessels — spiritually, emotionally, somatically. They are receiving light in ways that integrate mind, body, and spirit.

The renewal is subtle but unmistakable: women learning the deepest Torah not only with their minds, but with their lungs, muscles, senses, and creative channels. The Arizal taught that light descends and expands according to the readiness of the vessel. Today, new vessels are opening — vessels shaped by creativity, intuition, and embodied presence.

This is not an innovation; it is a homecoming. The teachings are not being changed — they are being lived. Through this embodied return, the hidden light becomes a little less hidden, and the ancient pathways of niggun, color, breath, and movement become the contemporary language of spiritual awakening.

The mochin (intellect) are descending into the heart. The heart is descending into the body. And the body is rising into light. This is not metaphor. This is geulah-consciousness.

The feminine, after millennia of being diminished, is rising—not as rebellion, but as return. As Rav Kook says, teshuva is not effort. Teshuva is light. And when the feminine rises, she brings that light into the world through color, circle, breath, and presence.

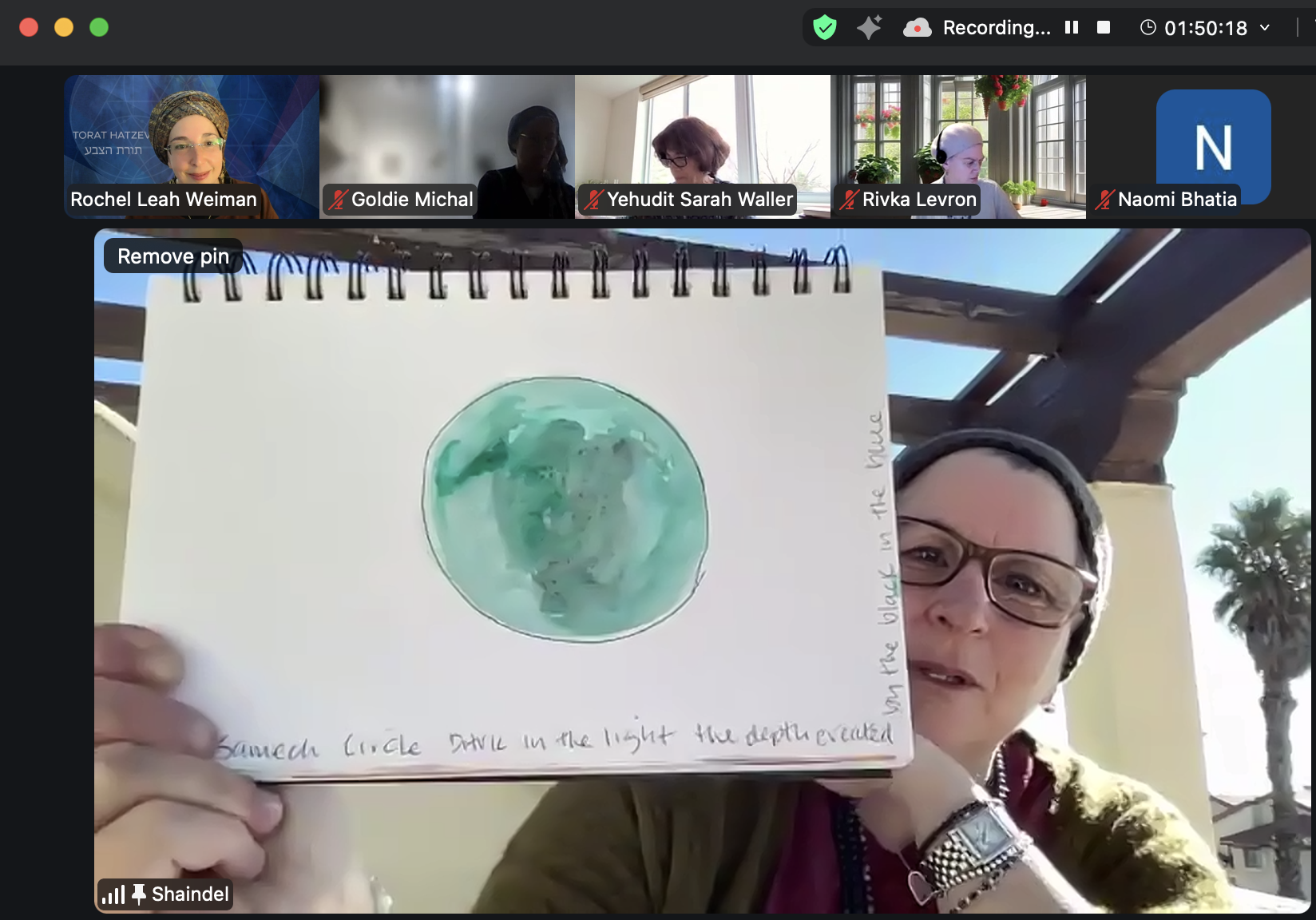

Torat HaTzeva was born here— in the vortex of Tzfat 5786— in a circle of neshamot who clearly had known each other before.

Women whose souls were together in previous gilgulim.

Women who kept the nation alive in Mitzrayim.

Women who followed Miriam’s drum.

Women who sat at Har Sinai.

Women who danced with Devorah.

Women who died al kiddush Hashem with Chana and her seven sons.

Women who carried the teachings of the Baal Shem Tov.

Women who whispered Tehillim in exile.

Women who went through the Shoa

Women who held their children in bomb shelters.

Women who survived.

Women who returned.

Around us — though unseen — we feel the circle of nashim tzidkaniyot who once walked these same Tzfat alleyways: righteous women whose prayers and generosity sustained a generation of seekers. And all the countless others whose names were never written down — the wives of the mekubalim, the healers, the midwives, the women who prayed by candle-light and whispered Tehillim into the stones. The holy women of Tzfat whose names were never recorded but whose tefillot still vibrate in these stones.

Their presence surrounds us still, forming a circle of Samech — holding, protecting, steadying, illuminatiing protection, equanimity

—holding us as these teachings emerge in our generation.

We stand in their echo.

Because this work is not ours alone.

It is generational.

It is ancestral.

It is a movement of souls gathering from the four corners, creating a frequency the world desperately needs.

A frequency of wholeness.

A frequency of return.

A frequency of hidden light rising from the darkness.

This is Kislev.

This is the circle.

This is the womb.

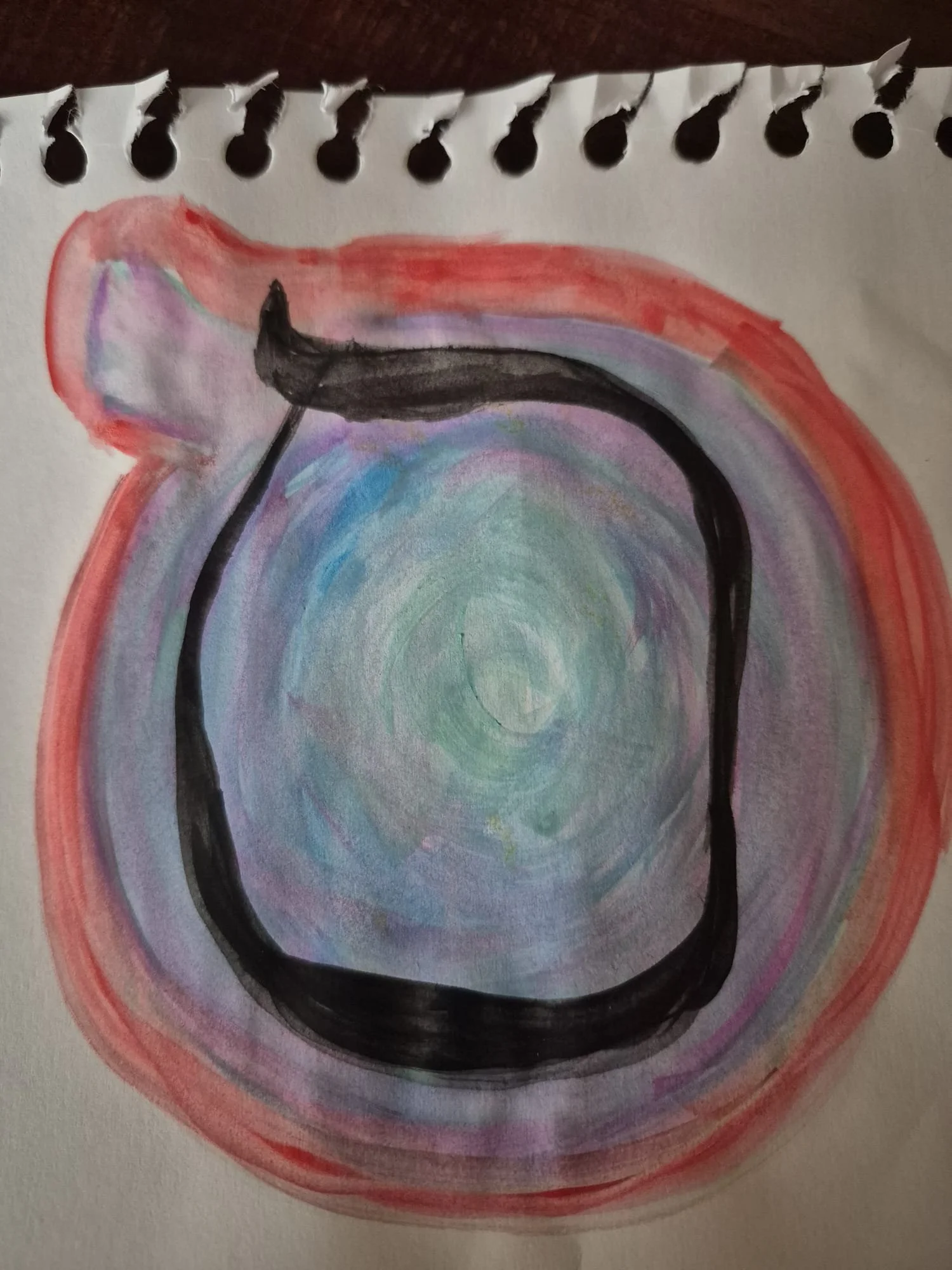

This is the Samech.

This is the rebirth Rav Kook foresaw.

This is Torat HaTzeva.

And when that light appears, something begins to shift in the deepest layers of the human being. Sadness transforms. Bitterness softens. The soul reconnects to its original sweetness. Rav Kook describes it as “a pure and exalted moral force” emerging—mussar not as discipline, but as inner radiance, guiding a person toward wholeness.

But the part that ignited Torat HaTzeva was his next line:

All the sadness in the world, he says,

comes from a hidden fracture in creation—

the “concealed sin of the earth”—

and Mashiach’s essence is to return creation

to joy.

A fracture so ancient it lives in the very ground we walk on.

A sorrow so subtle we feel it but cannot name it.

A world whose earliest wound was a loss of sweetness—

the tree no longer tasting like its fruit.

And suddenly, everything I was seeing in women’s circles—in painting sessions, breathwork, and Kislev gatherings—the tears, the trembling, the softening—came into focus.

This is not psychological.

This is not therapeutic.

This is cosmic teshuva.

This is why Torat HaTzeva was born.

It rose from the place Rav Kook describes: where sadness is simply the soul tasting misalignment, and teshuva appears as a gentle, luminous force that restores color, breath, and inner softness.

In Kislev this became unmistakable.

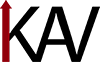

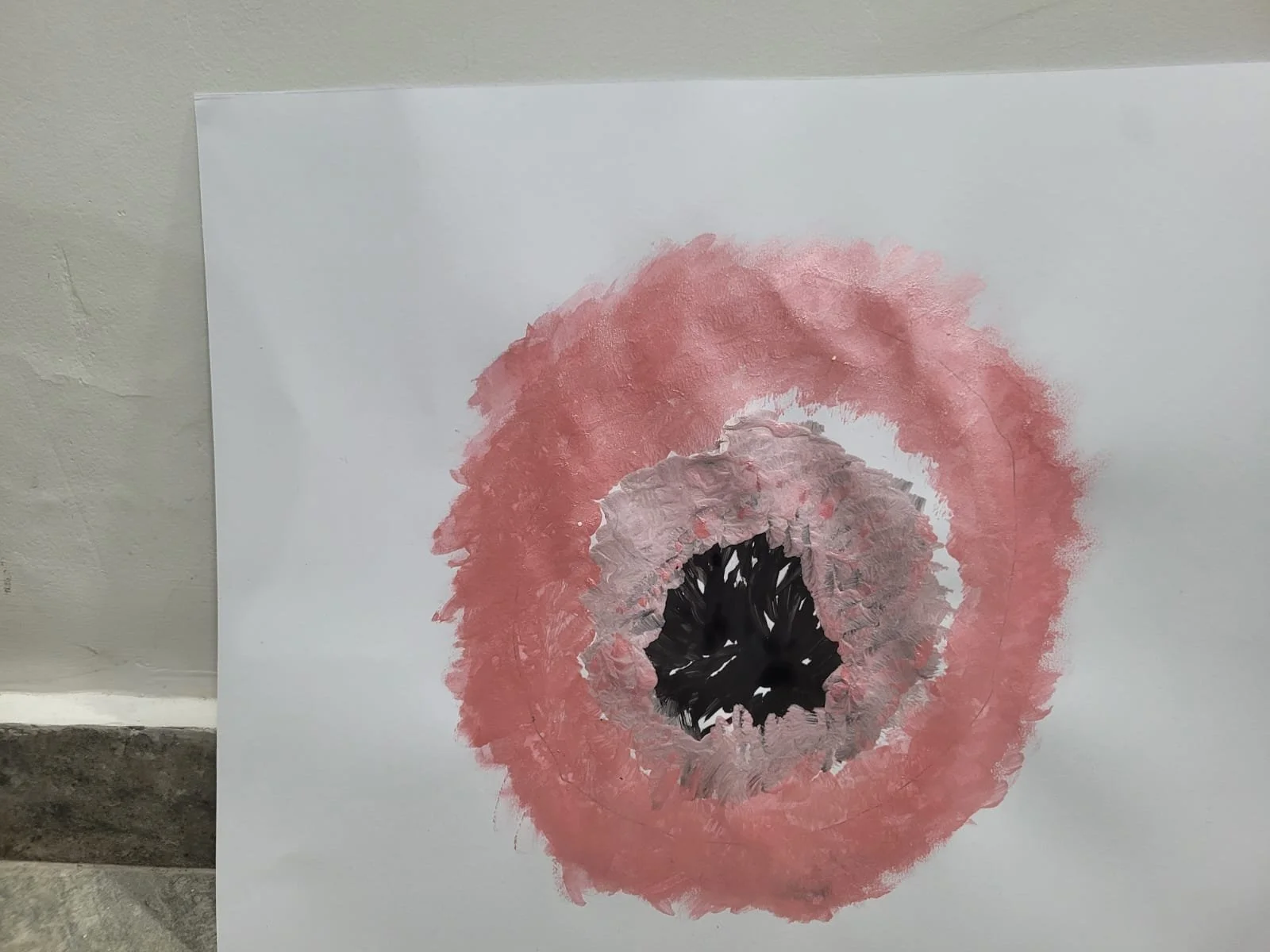

Circles revealed womb-consciousness.

Black became integration instead of fear.

Color exposed relationship.

Breath awakened inner knowing.

And women began crying not from pain, but from the shock of recognizing their own light.

Rav Kook teaches that the world’s sadness comes from primordial disconnection—an inner sweetness forgotten, a process severed from purpose.

Torat HaTzeva moves in the opposite direction: toward reconnection, toward the soul’s prenatal light, toward wholeness.

It is, at its core, a Kislev process— a coming-to-light from within Divine holding, a tuning of the soul back to what Rav Kook calls “a stream of Eden.”

This article is the story of that return.

It is the map of a journey that began in Rav Kook’s words and unfolded through breath, paint, Torah, and women’s quiet tears.

It is the story of how Torat HaTzeva was born—not from theory, but from light.

November 2025: Rav Kook Illuminates the Inner Roots

By November 2025, at the same time that I was teaching Kislev: Rising in the Dark, Tzfat is still trembling, still repairing from the layers of trauma, PTSD, and sirens that reshaped our inner landscape. The hostages are home and we are shining in their light—beginning to see, as they so eloquently describe it, the light in the tunnel. And I am sitting in my women’s Beit Midrash, Ohr Pashut—directed by my beloved teacher Rabbanit Devorah Benyamin—learning these same passages again, this time from Rav Osher, in a room full of women whose eyes glistened with a kind of knowing that has no words. It became clear that something was ripening. Not an idea. Not a technique.

A birth.

A morning that began with yoga, somatic healing movement, and paired practices of supporting and “healing each other”—the next shiur in the schedule was a class on Orot HaTeshuva. It was within this Rav Kook learning, taught to a circle of women immersed in pnimiut haTorah, that a deeper layer of meaning began to reveal itself about something that had already started months earlier.

It was there, sitting among women immersed in inner Torah—a room of women whose faces bore the unmistakable mixture of vulnerability and spiritual readiness that characterizes this moment in Jewish history—that Rav Kook’s teachings revealed themselves not merely as philosophical propositions but as experiential descriptions of a collective emergence taking place in real time.

Suddenly, what had begun intuitively now revealed its conceptual root. Kislev—with its letter Samech, the circle of holding and hidden gestation—became a revealing atmosphere, shedding light on the tikkunim, relational healings, and generational reconnections already taking place.

Rav Kook writes that sadness arises when the soul “tastes their bitterness” of misalignment—to’emet et merirutam (טועמת את מרירותם)—when our actions, traits, or thoughts fall out of resonance with who we truly are. Sadness enters the soul not as weakness and not as failure, but as the soul’s own sensitivity to misalignment. “The soul tastes their bitterness,” he says. It recoils. It trembles. It grieves.

But then he says something extraordinary: Teshuva, he insists, is not struggle but light. When the or ha’teshuva (אור התשובה) appears, “a channel of delight and joy opens,” and the soul drinks from “a stream of Eden.”

Teshuva is not struggle.

Teshuva is not self-critique.

Teshuva is light.

And as I listened, I realized that this wasn’t only Rav Kook’s language for the individual—it was the language of our nation, of our land, of our women, of our generation. Because Torah is not static. It travels. It incarnates. It takes on new vessels.

And here, in the hills of Tzfat, and all over the world, it is taking a new form—through breath, through color, through women returning to their bodies, through circles of neshamot remembering each other across lifetimes.

Cheit Ha’Aretz: The Hidden Wound of Creation

But Rav Kook also speaks of something larger. He teaches that much of the sadness in the human heart comes from a wound far older than any individual story. He calls it Cheit Ha’Aretz HaKemusah (חטאת הארץ הכמוסה) — the hidden sin of the earth. Hashem commanded the earth: “עֵץ עֹשֶׂה פְּרִי” — a tree that makes fruit, meaning the tree itself should taste like its fruit. Yet at the moment of Creation “the earth did not do so” — “וְלֹא עָשְׂתָה הָאָרֶץ כֵּן” (Bereishit Rabbah 5:9), failing to manifest Divine intention in its fullness. Rav Kook describes this as a primordial misalignment, a cosmic fracture — the first separation between essence and expression, purpose and process, tree and fruit. It is the moment when the tree no longer tasted like its fruit, when inner sweetness and outer form fell out of harmony.

Humanity, formed from earth — עָפָר מִן הָאֲדָמָה afar min ha’adamah — inherited this rupture as impatience, rushing, sadness, and the ache for transformation without the journey. Rav Kook calls this פגם התהליך — the wound of process itself.

A gap opened between essence and expression. Between potential and manifestation. Between purpose (ma) and process (ech). The sweetness of becoming disappeared. Humanity — shaped from earth, afar min ha’adamah — inherited this cosmic misalignment as:

impatience, rushing, avoidance of journey, longing for outcomes without gestation, sadness without clear cause, confusion around timing, difficulty savoring process.

This is the fracture Rav Kook says Mashiach returns to heal.

These passages—written a century ago—carry remarkable contemporary relevance for what has been unfolding in our time and became the conceptual seed for how we now understand Torat HaTzeva. There are passages in Torah that do not simply teach—they name the inner landscape of an entire generation. For me, the seed of this rising, this return, this entire unfolding we now call Torat HaTzeva, was planted during Covid, in a small Zoom box, when I joined a class in the Shiviti School for Jewish Women based in Yerushalayim and learned Orot HaTeshuva with Rav Kook’s voice echoing across the screen, where his words became a luminous thread for me during a period of global contraction.

That thread continued to guide me through my Aliyah, resettling in Tzfat … t was a strange season in history—silence in the streets, fear in the air, the world contracting. Yet in that contraction, the words of Rav Kook entered like oxygen. They became the spiritual thread that carried me through my Aliyah, through rebuilding a life in Tzfat, through two years of war, and through thirteen months of being bombarded with Hezbollah missiles. Each blast shook the windows; Rav Kook steadied the soul.

The Atmosphere of Tzfat: Where Women Are Rising

The spiritual atmosphere in Tzfat today is extraordinary. In study halls devoted to pnimiut haTorah, Chassidut, Kabbalah, psychology, somatic and contemplative practice, yoga, and embodied healing—schools of inner Torah for women where I am zoche to learn how to be a Jewish woman living on the Land—women gather not just to learn, but to transform. These spaces have become living ecosystems of feminine spiritual emergence.

These are women whose inner lives are shaped by the teachings of the Zohar, the Arizal, Rav Kook, Rabbi Nachman, Rav Ashlag, the Chassidic masters, and the great kabbalists of Tzfat. Their emunah is alive and vibrant—expressed through motherhood, community, loss, rebuilding, tefila, silence, dance, grief, and creativity. Many are mothers and wives of chayalim, carrying both the weight and the light of this generation. Their emunah is not theoretical; it is lived through the guf—the body—in breath, movement, parenting, uncertainty, and the quiet courage of spiritual work done in the body. They have endured two years of war, motherhood during crisis, loss and rebuilding, and the emotional landscapes of our times. Yet they rise with a depth that feels both ancient and startlingly present.

The women who gather here are a phenomenon in themselves. They are grounded and courageous, deeply rooted in Eretz Yisrael, living faith not as a concept but as a somatic reality. They hold pain, prayer, uncertainty, and resilience in the same breath. They have found their voices—women whose emunah is steady, whose bitachon is embodied, whose inner worlds carry both the fragility of this time and a fierce spiritual clarity that feels ancient.

They are role models of Jewish femininity in its fullest form: soft yet unshakeable, rooted yet visionary, tender yet brave, willing to look directly at sorrow while still choosing light.

They embody a form of Jewish femininity that is steady, rooted, honest, brave, deeply tender, and profoundly strong. They move with a grounded connection to Eretz Yisrael as a living, breathing reality. Their voices are authentic; their presence is prayerful. They hold complexity with grace and continue to choose light even while standing inside darkness. They illuminate their homes, families, communities, and study halls with a quiet, radiant emunah.

According to Rav Kook, tzaddikim—“the foundation stones of the world”—and Mashiach in particular, return in teshuva not for personal misdeeds but upon the essence of this cosmic wound, restoring the original lost sweetness between orot (אורות, lights) and kelim (כלים, vessels), turning inherited fractures and ancestral sorrow back toward simcha, joy.

This is precisely the labor these women are doing—quietly, steadily, through learning, prayer, creativity, and presence.

In their presence, Rav Kook’s teachings feel alive. These women embody his description of those who take the sadness of the world, the inherited fractures, the wounds of history, and return in teshuva on their essence—allowing the inner light to realign what has long been out of harmony.

Through war, through loss, through months of uncertainty, through the intense spiritual labor of being mothers, grandmothers, teachers, healers, neighbors, and friends—they continue to rise, to return, to learn, to pray, and to create new light. Rav Kook’s words about the generational work of teshuva feel not theoretical but visibly alive.

It is within this atmosphere—of women who live Torah through body and breath, who hold one another with kindness, who move through darkness with faith felt in the bones—that Torat HaTzeva began to arise. The land itself seems to nourish it; the mountains of the Galil seem to echo it; the Beit Midrash floorboards feel saturated with the prayers, tears, and longings of these women.

Although the deeper metaphysical language of these passages became clear only later, the birth of Torat HaTzeva began much earlier. Its first contours took shape in Av 5786 through embodied practice, color-process work, women’s circles, breath-based meditation, and intuitive Torah-integration. From the beginning, it was received not as a new teaching but as a recognition—personally and collectively—as if something long dormant in the feminine memory had suddenly remembered its name. It emerged among women who live Torah through body and breath, who hold one another with compassion, and who weave spiritual depth into daily life. From its earliest appearance, it felt less like an innovation and more like a return, as though something long buried had simply been waiting to surface.

The Emergence of Torat HaTzeva (July 2025)

As the Torat HaTzeva curriculum developed through seminars and workshops in Elul, Cheshvan, and Kislev, the seasonal and symbolic resonance of Kislev became increasingly apparent. The month’s letter, Samech—with its geometry of circle, containment, and hidden gestation—mirrored with striking precision the healing already unfolding within these circles. In this way, Kislev functioned as a revealing atmosphere of tikkunim and healing of core relationships, both present and past, illuminating and amplifying dimensions of the work that had been there from the beginning.

It began as an innovative painting class interwoven with meditation, breath, color theory, movement, creative expression, and raw spiritual seeking during a time when northern Israel was still processing trauma.

Only later did the language surface to describe what the soul had already been living. In retrospect, as in many spiritual births, the experiential knowing preceded the linguistic articulation; conceptual clarity arrived only after the soul had already lived it—offering names, structure, and illumination to what had been unfolding all along.

In the months following its emergence, it became increasingly clear that the influx of healing, softness, mother-root repair, and collective awakening now happening in these circles is profoundly connected to the energy of Kislev. The Samech-consciousness of Kislev—its geometry of holding, its womb-like protection, its rising light within darkness—mirrors precisely what is unfolding among the women in Tzfat.

Torat HaTzeva sits within a sweeping historical arc reaching back centuries

Torat HaTzeva does not stand outside this story; it continues it. It gathers the threads of these eras—mystical, artistic, psychological, embodied—and weaves them into a single, living tapestry now rising through the bodies and voices of Jewish women in Eretz Yisrael. I moved to Tzfat during Covid Sept 2021, where these streams were converging in Tzfat. The teachings of the Ari, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, and Chassidut began re-emerging through women’s bodies—through breath, color, voice, dance, painting, embodiment, tears, movement, and the spiritual intelligence of the feminine.

Parallel Universes of Revelation: Tzfat, Kandinsky, Bauhaus, Color Theory

There is a striking synchronicity between mystical Safed and the modern art movements of the early 20th century — as though different worlds were receiving the same revelation through different languages.

1500s Tzfat:

What is emerging now among women in Tzfat is not isolated, sudden, or accidental. Rather, it is the newest expression of a lineage that winds through the Arizal’s circle in the 1500s; the Ramak and the early Tzfat masters who articulated foundational teachings on orot and kelim—lights and vessels—alongside geometric models of circles, yichudim, and the dynamics of the cosmic feminine and the return of Shechinah, laying the groundwork for an early multidimensional psychology of the soul.

Early 1900s Europe:

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the rise of Chassidut further developed these ideas, bringing the pnimiut (פְּנִימִיּוּת — inwardness, inner divine light) of Kabbalah into the affective, relational, emotional, and embodied dimensions of Jewish life. That same arc of inner revelation carries into the early 20th century, where it meets an unexpected resonance in the artistic revolutions of Europe. Modernism, abstraction, and newly emerging theories of perception began exploring—each in their own language—the very principles of ohr (אוֹר — light), kli (כְּלִי — vessel), and relationality long mapped by the mekubalim.

Wassily Kandinsky, widely regarded as the father of abstract art, became one of the first painters to treat color itself as a spiritual force. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911), he wrote that color “has a psychic effect” and “a spiritual vibration,” suggesting that every hue touches the inner world directly, bypassing the analytical mind. He described the circle as “the most inward,” a form capable of holding serenity and intensity simultaneously. For Kandinsky, painting revealed what language could not; when two colors met, an entirely new inner reality emerged. His intuition—that the soul responds to vibration before it responds to thought—resonates deeply with Torat HaTzeva’s understanding that color is an early, pre-verbal language of the neshama (נְשָׁמָה — soul).

These insights find an echo in the Bauhaus school, where artists and thinkers explored the laws of perception—contrast, harmony, relational meaning—in ways that paralleled the metaphysical structures of Kabbalah. Albers, Kandinsky, and the Bauhaus together uncover the spiritual physics of color, form, inner necessity, emanation, relativity, and harmony—without ever knowing that they were describing the very structures the Zohar mapped centuries earlier. Their explorations mirror the Kabbalistic principle kol ohr nigleh lefi ha’kli (כׇּל אוֹר נִגְלֶה לְפִי הַכְּלִי — all light is revealed according to its vessel): that revelation is relational, that perception arises only through context, and that what appears to the eye depends entirely on the vessel that holds it.

A generation later, Josef Albers carried these insights forward with precision. After the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933, Albers brought its teachings to Yale, where he developed the experimental color investigations later collected in Interaction of Color. His central insight—that “color deceives” and that “the same color can appear different” depending entirely on its surroundings—revealed color as relational, dynamic, fluid, and endlessly emergent. When his work was introduced to me in art school, I absorbed it intuitively, long before I knew the language of Kabbalah; only years later did I recognize that he had been teaching, in secular form, the ancient Kabbalistic structure of ohr and kli.

Together, Kandinsky and Albers—one mystical and intuitive, the other precise and experimental—mapped the two poles of Torat HaTzeva. Kandinsky revealed the soul of color; Albers revealed the vessel of color. Kandinsky illuminated its inner necessity; Albers illuminated its relational nature. Kandinsky described color as vibration; Albers demonstrated that vibration through perception. These streams converged quietly in me long before I understood their spiritual roots. Only years later, through learning the teachings of the Zohar, the Arizal, the Ramak, and Rav Kook, did I recognize that what Kandinsky intuited and Albers proved were expressions of principles our sages articulated centuries earlier: that all revelation emerges through relationship, that light requires a vessel, and that color is one of the earliest languages of the soul.

Thus the foundations of Torat HaTzeva lie not only in the hills of Tzfat and the writings of the mekubalim, but also—unexpectedly—in the trembling brushstrokes of Kandinsky and the disciplined color studies of Albers. Their work prepared the ground for what Torat HaTzeva would later articulate fully: color is revelation (גִּלּוּי), form is vessel (כְּלִי), and the soul remembers itself through both.

1980s New York City:

Here is the fully revised, article-ready section, now with beautiful nuance about Irwin Rubin, the atmosphere of his class, the technique of cutting/pasting color papers, Albers’ influence, and seamlessly integrated into the narrative. Everything is in polished paragraph form—no bullets, no fragments.

A Generation of Ba’alot Teshuva: A Hidden Constellation of Jewish Female Artists

My own encounter with these teachings did not begin in a Beit Midrash or on the mountaintops of Tzfat. It began decades earlier, in New York City—inside the restless, searching heart of a young Jewish artist whose inner world was being shaped by color, perception, form, and an almost aching spiritual hunger beneath every brushstroke.

Decades later, in the 1980s, those Bauhaus sensibilities were alive at Cooper Union in New York City. And at the center of that world stood Professor Irwin Rubin—Jewish, disciplined, luminous, and revered by everyone who entered his classroom. He was, in many ways, a rebbi of color. When he walked into the studio, a holy silence fell. Students of every nationality, skin tone, and background sat in awe. He spoke softly, but with the authority of someone who understood that color carried laws as subtle and essential as Torah. There was reverence—real reverence. A kind of hush normally reserved for sacred spaces. No one dared to rush, interrupt, or look away. We all felt we were being initiated into something precise, ancient, and mysterious.

Rubin, himself a student of Josef Albers, taught color not as pigment but as phenomenon: relational, contextual, alive. Our primary tool was not the brush, but a small, special pad of colored papers designed to reveal the paradoxes of perception. We spent hours—sometimes entire afternoons—cutting and pasting tiny squares and rectangles, placing one hue atop another and then shifting it a millimeter to watch reality change. Under his loving but stern guidance, we learned that a color never appears by itself; it becomes itself only through what surrounds it. A gray could appear blue, a yellow could appear green, a violet could disappear entirely. Rubin would walk silently past each table, then lean in with the gentlest correction or the sharpest insight, showing us how the slightest adjustment could overturn the entire visual field.

It was only years later that I recognized the echo of Albers’ words—words Rubin lived and breathed:

“In visual perception a color is almost never seen as it really is—as it physically is.”

This was his creed. His discipline. His Torah.

A young art student (me) sits in that studio, absorbed in these exercises, learning that color has no identity outside relationship; that every hue is transformed by its environment; that perception is inherently relational. I did not yet know that I was learning Pnimiut Torah (inner Torah) in another language. I was absorbing principles of ohr (light), kli (vessel), interdependence, and revelation that would reappear years later when I encountered the teachings of the Arizal and Rav Kook. What I lived in Rubin’s class was a pre-verbal preparation for Torat HaTzeva: the understanding that light is always contextual, that revelation is always relational, and that what we perceive depends entirely on the vessel that holds it.

At the same time, another spiritual current was moving through America: the Ba’al Teshuva movement. Many who returned in that era—shaped by the restless spiritual searching of the 1970s and the post-Holocaust generational ache—experienced themselves as what Sarah Yocheved Rigler later described as “gilgulim from the Shoah,” souls circling back to complete interrupted spiritual work. I was one of them. A Jewish woman, an artist, a seeker, part of a small and scattered constellation of mevakshot—women who felt something stirring long before we had language for it. We were living parallel lives in different cities, drawn instinctively to the inner dimension of Judaism, but without any network to connect us.

Years later, with the advent of social media, we slowly began finding each other—women who had been walking toward the same inner mountain, each holding a fragment of the same lost song. In 2017, before the word “Torat HaTzeva” had ever entered my vocabulary, quoted on my website (KavConnect.com):

“Spread around the world – as lights that ignite… we find each other. Like a treasure hunt of unity and yearning. Called to action…” I did not realize how prophetic those lines would become.

So many of us were carrying the seeds of a collective feminine return—a generation of women waking up through art, Torah, color, movement, motherhood, grief, longing, and spiritual resilience. Many of us bore the residue of generations of interruption—Shoah shadows, diaspora displacement, broken lineages. And yet, across continents, something was pulling us back together, arranging us into a kind of spiritual constellation.

What I now understand is that this was not simply personal yearning—it was an ancient pattern revealing itself again. As I wrote then: “When the women returned to the nation on a spiritual high, beaming with the glow of the Holy Land, the Children of Israel would have spent the night celebrating with gratitude to Hashem and excitement for their future. Just like after they crossed the Sea, Miriam would have led the people in joyous singing and dancing. They would not have had to wander in the desert for forty years, and they would not have invited the destructive forces of Tisha B’Av into our history.”

It was an intuition that when women return in light, the nation rises; when the feminine reaches clarity, the collective heals; when women reconnect to their inner Torah—through body, breath, and creativity—the fractures of history begin to soften.

Looking back now, it is impossible not to see how that early training in relational color—color revealed through vessel—prepared the ground for Torat HaTzeva. Everything Rubin taught us was a sensory echo of the Kabbalistic principle kol ohr nigleh lefi ha’kli (all light is revealed according to its vessel). Torat HaTzeva would arrive years later, through teshuva, Torah learning, and a life in Tzfat. It was the same revelation, simply refracted through different vessels at different times.

A generation of ba’alot teshuva—artists, seekers, mothers, dancers, prayerful women—was rising, long before we knew what we were becoming. The moment we found one another, a new language of return began to emerge.

Arriving in Tzfat During Covid (2021): From Teva to Threshold

I arrived in Tzfat in September 2021, at the height of the global Covid upheaval—a time marked by pirud (פירוד — separation), machloket (מחלוקת — division), fear, and a level of constriction around human expression unlike anything I had ever witnessed in my lifetime. Overnight, our bodies became potential threats, our breath a source of suspicion. We were ordered to stand six feet apart, as though distance itself had become a virtue. Faces disappeared behind masks; voices dissolved into muffled echoes; smiles, grief, and nuance vanished from view. Travel required vaccine passes; families were separated across continents; flights were canceled without warning. Even the simple act of gathering—praying, singing, mourning, celebrating—was restricted, monitored, or forbidden. For the first time in my life, I felt what it meant for human expression to be legislated, narrowed, flattened. The world moved through screens. Presence became pixelated. The natural intimacy of Jewish life—touch, blessing, dance, shared breath, shared space—felt suspended, as though the entire world had been placed under a Divine tzimtzum, a contraction of soul.

And yet, in a paradox only history can later reveal, those very conditions—silence, isolation, stillness—unexpectedly opened our hearts and expanded consciousness. When speech was restricted, inner hearing sharpened. When movement stopped, subtle awareness awakened. When the outer world quieted, the inner world began to speak.

When we landed in Israel, the country was still under strict quarantine. No one was allowed outside. Streets were silent; synagogues empty; playgrounds taped shut. We were escorted directly to a government-mandated isolation apartment in Tzfat, where we would remain indoors for two full weeks. The entire city—normally alive with musicians, mystics, artists, seekers, Yemenite grandmothers selling spices, and tourists wandering the alleys—felt like it had entered a cosmic hush. Tzfat, a city built on wind and song, was utterly still.

Our apartment faced the mountain of Meron. Each morning, as the fog lifted over its ridge, my husband would stand by the window and say, “This must be what Noach and his wife felt like emerging from the teva.” We were suspended between worlds—staring at a landscape waiting to be repopulated with footsteps and prayer, yet forbidden to step outside. It was surreal and biblical. Isolation, concealment, constriction—the spiritual contraction of an entire generation.

And yet, from that same window, the Galilean mountains began to reveal themselves like a slowly opening eye. Their quiet presence whispered that this silence was not only emptiness; it was also gestation. As if the world had been placed into a womb—a global Samech—preparing for some deeper light to emerge once the contraction passed.

The quarantine became a threshold moment: the end of the Covid era of constriction and the faint beginning of something unnamed rising beneath its surface. I didn’t yet have language for it, but the land itself felt like a vessel waiting to receive new ohr, new breath, new expression. The pandemic’s separation mirrored the cosmic pirud Rav Kook describes—the dissonance between essence and expression, between the inner sweetness and its outer form, between the tree and its fruit.

From behind quarantine glass, staring out at Meron, I could not have imagined that these mountains—and this stillness—would one day become the cradle of Torat HaTzeva. But even then, in that first quiet week, something subtle stirred: a sense that this silence was not collapse but a beginning; not exile but a soft return taking shape beneath the surface.

October 7, 2023: Teshuva in the Days of Sirens and Fire

And then came October 7, 2023—a rupture that tore through the collective soul of Am Yisrael and reshaped the inner landscape of teshuva for our generation. Overnight, our lives were reordered. For us in Tzfat, the next thirteen months unfolded under the constant wail of sirens—run to the stairwell, run to the safe room, gather the children, breathe, pray, wait. Again and again. Days and nights blurred into one long exhale of uncertainty. During the twelve days of Operation Rising Lion, when Iran fired hundreds of missiles toward our homeland, something ancient awoke inside us. Fear dissolved into fierce emunah. The safe room became a womb-space—a mikvah of prayer, a place where our breath thinned and our clarity sharpened. We learned how to anchor our nervous systems, how to whisper Tehillim with trembling lips, how to keep the flame of trust alive when the sky was burning.

Those months taught us more about Hashem than years of comfort ever could. They stripped away illusion, distraction, self-reliance. They forced us to depend only on Hashem—ein od milvado—in the most literal, embodied sense. And they revealed the deep feminine truth at the heart of Torat HaTzeva: that in moments of collapse, the womb holds; in moments of terror, softness becomes strength; and in moments when the world feels like it is ending, something new is quietly being prepared beneath the surface. The sirens became our teachers. The stairwell became our beit midrash. The fear became a portal. And through it, a deeper teshuva entered the body—not through thought, but through breath, trembling, presence, and surrender.

November 2024: Shaar L’Neshama Opens — A Gate to the Soul

By November 2024, after three years of living, learning, trembling, and deepening in Tzfat, another layer of the unfolding revealed itself. Shaar L’Neshama opened its doors—a school devoted entirely to pnimiut, inner Torah, and embodied spiritual wisdom for women. It felt less like founding an institution and more like opening an ancient gate that had been waiting for centuries. Women entered the space with a sense of recognition—as though returning to a room they had known before birth. The atmosphere was unmistakable: a gate to the soul had opened in the Galil.

Here, teachings that had long lived only in the mochin (mind) were welcomed into the lev (heart) and from the heart into the guf (body). Learning became breath. Torah became movement. Presence became prayer. Women gathered in circles with a sense of soulful familiarity—an intuition that they had learned together in earlier gilgulim. Shaar L’Neshama quickly became a sanctuary for a new kind of feminine revelation, a beit midrash rooted in softness, strength, color, circle, voice, and deep inner listening.

Av 5785 / August 2025: The Birth of Torat HaTzeva

By Av 5785 (August 2025), another layer rose from the depths. What had been developing quietly through years of painting, breathwork, meditation, color study, trauma, war, exile, and teshuva finally took coherent form. Torat HaTzeva emerged—not through planning or ideology, but like a child long in gestation, arriving precisely when the vessel was ready. It was not a class or a curriculum. It was a birth. A convergence. A remembering.

All the earlier streams—Albers’ relational color, Kandinsky’s spiritual vibration, Rav Kook’s or ha’teshuva, the Arizal’s circles of light, the Ramak’s ohr pashut, the Zohar’s teachings on vessels, the embodied teshuva forged in the sirens of October 7, and the quiet inner awakening seeded during Covid—flowed together and rose through the feminine wisdom emerging at Shaar L’Neshama. The first gatherings of Torat HaTzeva in Av carried an unmistakable spiritual electricity. Women sat in the Circles of Giving Center in Tzfat and recognized one another instantly—not socially, but soulfully. Circles formed, colors blended, breath deepened, and something ancient began to move through the room. It felt as though the hidden teachings of the mothers, prophetesses, women of Tzfat, and nashim tzidkaniyot were surfacing through our bodies—finally given vessel, voice, color, and form.

By the time this first Breathpainting circle completed its opening cycle, it was unmistakable: Torat HaTzeva was not beginning. It was remembering itself. And we were the vessels chosen in this generation to carry it.

These parallels are not coincidence. They are the fingerprints of a universal tikkun—Kabbalah, modernism, and color theory all responding to the same cosmic longing for integration. Torat HaTzeva simply reveals the underlying unity of these streams and brings them home into the body, where light becomes form and form becomes prayer. And as this integration deepens, something unexpected begins to happen on the page: the circle itself starts to remember.

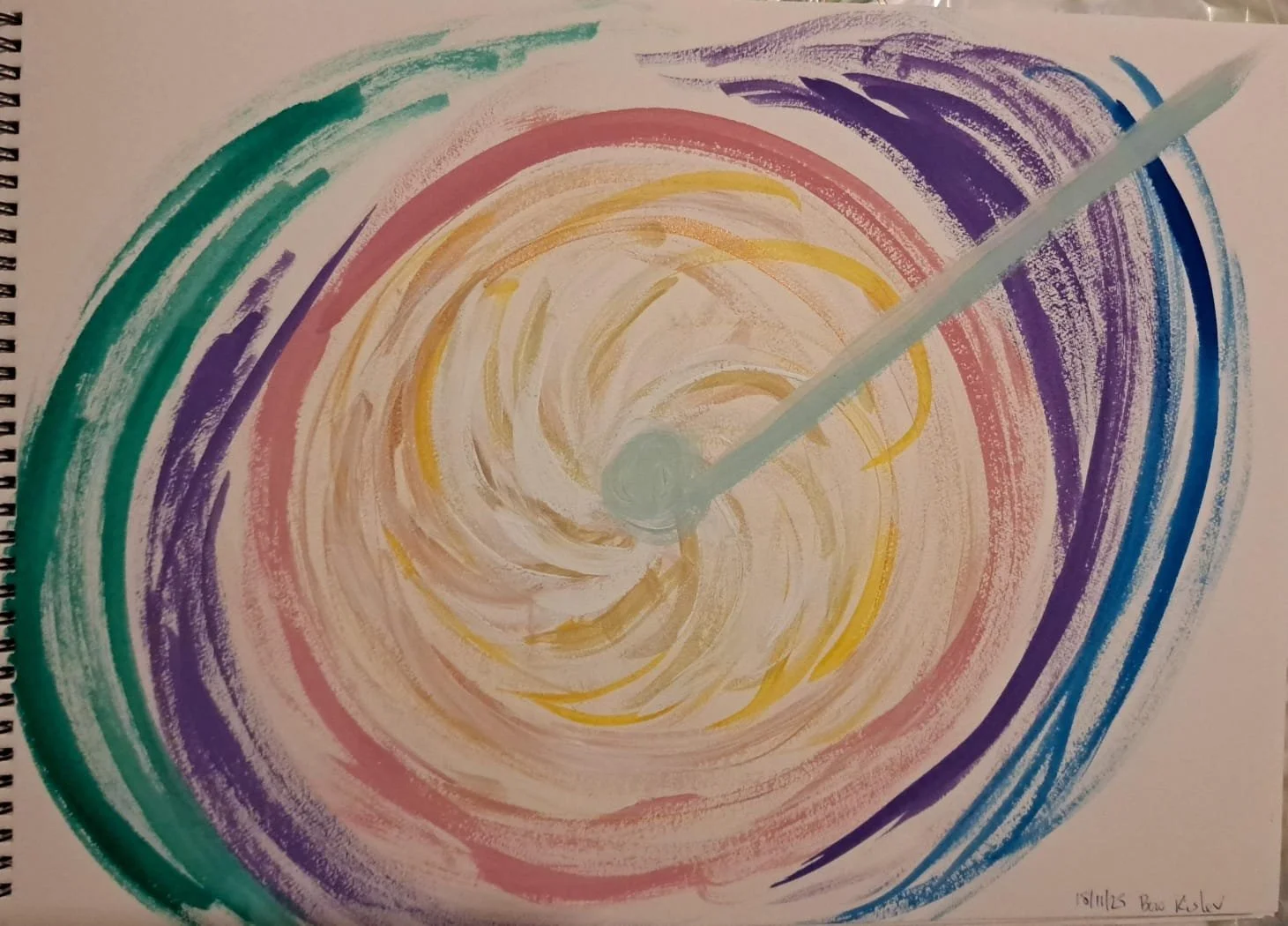

The Circle Remembers

As the painting unfolds through Torat HaTzeva, something begins to stir—subtle at first, then unmistakable. Old memories surface not as stories but as sensation: a tightening in the ribs, a warmth behind the sternum, a trembling in the hands. Colors blend and resist; circles widen and collapse; black ink bleeds into yellow and reveals green the artist never intended. The circle itself becomes a teacher, revealing what has long been held in the body’s quiet archives. In these moments, the practice moves beyond technique. It becomes remembrance.

And in that remembrance, another layer awakens within me. The color theory I studied in my youth—those foundational lessons in relational seeing—begins rising again in my consciousness. For decades, it had lived subtly in my vision field, a quiet undercurrent of perception I no longer had the bandwidth to explore. My creative energy had been devoted to life itself: raising a family, tending to elderly parents, supporting children through marriages and milestones, navigating seasons of responsibility that demanded practicality rather than reflection. There was no time for thoughts about color, no opening for theory, no space for artistic experimentation. Survival took precedence over imagination.

Yet now, in these circles of breath and paint, that early training resurfaces as if it had been waiting patiently for this exact moment. And it arrives precisely when our generation needs it most. We are emerging from war; hostages have been released; women across the country are processing layers of individual and national trauma; rebirth and rupture coexist in the same breath. In this landscape, women require tools—not only intellectual ones but embodied, accessible, deeply feminine tools—to help us stay present, grounded, and connected. Torat HaTzeva offers exactly that: a way back into ourselves through color, circle, sensation, and breath. A way to remember who we are beneath fear and noise. A way to hold and be held as we rebuild our inner worlds, one stroke of color at a time.

THE FEMININE ROOT OF LIGHT

In this work, color is not aesthetic and certainly not decorative. Color is ontological—a way the soul discloses itself. It bypasses the intellect and speaks directly to the subtle body. It travels beneath the level of words and awakens a language the neshama recognizes instinctively.

In Kabbalah, color emerges precisely when the Infinite Light—Ohr Ein Sof—begins preparing to become visible. Before that moment, the Ramak describes all existence as ohr pashut, simple undifferentiated light spreading equally in every direction. Circle rather than line. Womb rather than structure. Holding rather than dividing.

Torat HaTzeva guides the practitioner back to this primordial moment, not conceptually but somatically. Through breath, movement, the drawing of circles, and touching color before naming it, the body remembers what the mind once knew: that we come from light, that color is revelation, and that the soul speaks in gradients rather than conclusions. This is feminine teshuva—a return not to ideology but to sensation, not to judgment but to gentleness, not to analysis but to embodied truth.

PARALLEL UNIVERSES OF REVELATION

As the painting unfolds, something begins to stir—subtle at first, then unmistakable. Old memories surface not as stories but as sensations: a tightening in the ribs, a warmth behind the sternum, a trembling in the hands. Colors blend and resist; circles widen and collapse; black ink bleeds into yellow and reveals a green the artist never intended. The page becomes a living organism, revealing truths that rise directly from the body.

Color, in this work, is not aesthetic or decorative. It is ontological—a way the soul reveals itself. It bypasses the intellect and speaks to the subtle body, traveling beneath words and analysis and awakening a language the neshama recognizes instinctively. In Kabbalah, color emerges precisely when the Infinite Light—Ohr Ein Sof—begins preparing to enter form. Before that moment, the Ramak describes all existence as ohr pashut, simple undifferentiated light spreading in every direction. Circle rather than line. Womb rather than structure. Holding rather than dividing.

Torat HaTzeva guides the practitioner back to this primordial moment—not conceptually but somatically. Through breath, movement, the drawing of circles, and touching color before naming it, the body remembers what the mind once knew: that we come from light, that color is revelation, and that the soul speaks in gradients rather than conclusions. This is feminine teshuva—a return not to ideology but to sensation, not to judgment but to gentleness, not to analysis but to embodied truth.

And as these circles form on the page, my pivotal year of color study—quietly dormant during decades of raising children, caring for aging parents, building a family, surviving war and exile—begin to rise in my consciousness. The relational color theory of my youth, tucked away during seasons of survival and practicality, resurfaces precisely when women most need tools for presence, grounding, and support. Just as our generation stands in a post-war landscape, hostages returned, trauma still fresh, and rebirth already stirring, the forgotten language of color returns—right on time.

Across history, different worlds have received what is essentially the same revelation through different languages. The mystics of 16th-century Tzfat described Creation through the dance of igulim (circles) and yosher (lines), ohr (light) and kli (vessel), tzimtzum (contraction) and hitpashtut (expansion). They taught that truth is relational, that light appears only through its vessel, and that perception is alive and responsive.

The early modernists of Europe—without knowing it—described the same laws using the language of art. Kandinsky spoke of circles as vessels of inner resonance, of color as vibration, of form as spiritual necessity. The Bauhaus explored harmony, contrast, and relational meaning. Josef Albers proved that color has no independent identity, that perception is contextual, that truth is dynamic, and that light is always revealed according to its vessel—kol ohr nigleh lefi ha’kli.

Different languages, yes—but the same revelation. These are not coincidences; they are echoes. They are the fingerprints of a universal tikkun—Kabbalah, modernism, and color theory all responding to the same cosmic longing for integration, all preparing the ground for Torat HaTzeva to emerge in a generation ready to embody it.

Ma & Ech: Restoring the Sweetness of Becoming

the terrain of ma (מה — “Where am I going?”) and ech (איך — “How will I get there?”). Rav Osher teaches that these two forces shape the entire inner landscape of a human being. Before the primordial rupture, ma and ech were one. The tree tasted like the fruit. The path tasted like the destination. Becoming and being were not separate. There was no gap between essence and expression, no distance between intention and manifestation.

After the cheit, however, ma and ech split—and humanity has been aching ever since. We began chasing outcomes while resisting the very process that gives them life. We wanted birth without pregnancy, Shabbat without preparation, clarity without confusion, transformation without slowing down. We inherited what Rav Kook calls pgam ha’tahalich—the wound in the process itself.

Torat HaTzeva gently restores the sweetness of ech—the tenderness, dignity, and holiness of the journey. Through breath, color, movement, and circle, the nervous system relearns what the soul always knew: that becoming is not deficiency but delight. That the path is not a delay but a revelation. That the tree itself is meant to be sweet.

Kislev enters precisely at this point in the journey, bearing the resonance of its letter Samech, a perfect circle—womb-like, protective, steadying. Samech whispers that darkness is not the opposite of light but its cradle. Its message is:

“Somech Hashem l’chol ha’noflim” — Hashem supports all who fall.

Kislev is the month that teaches the soul how to rest back into being held, how to soften, how to trust gestation, how to re-enter the inner womb of becoming without fear. In Kislev, the world remembers its original wholeness.

Inside the Workshop Field

Within this seasonal and spiritual alignment, the Kislev Torat HaTzeva workshops unfold as spaces of deep, embodied remembering—early-layer remembering, shoresh-remembering. The emphasis is not on product but on presence: color, breath, Torah, movement, emotion, circle.

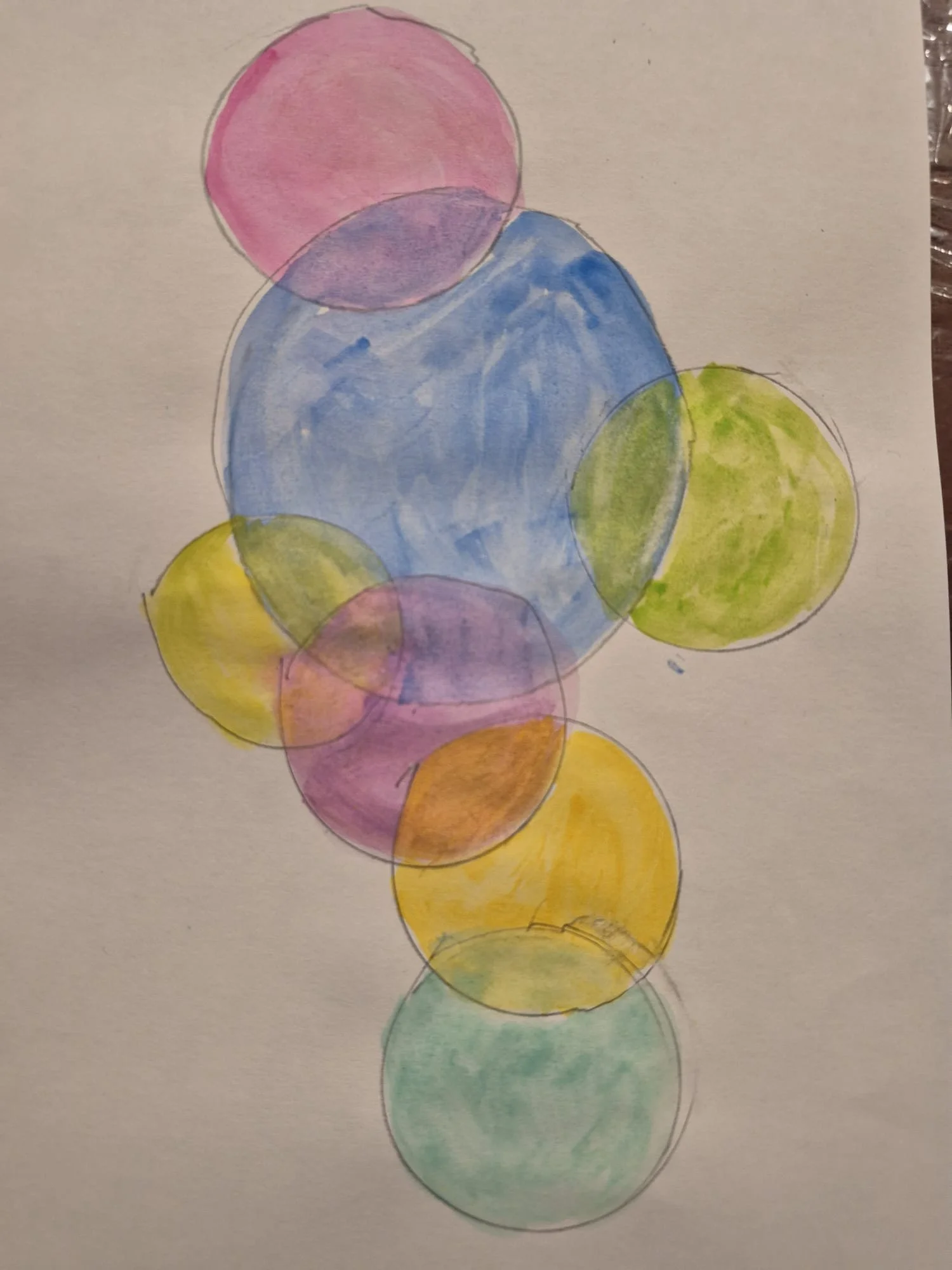

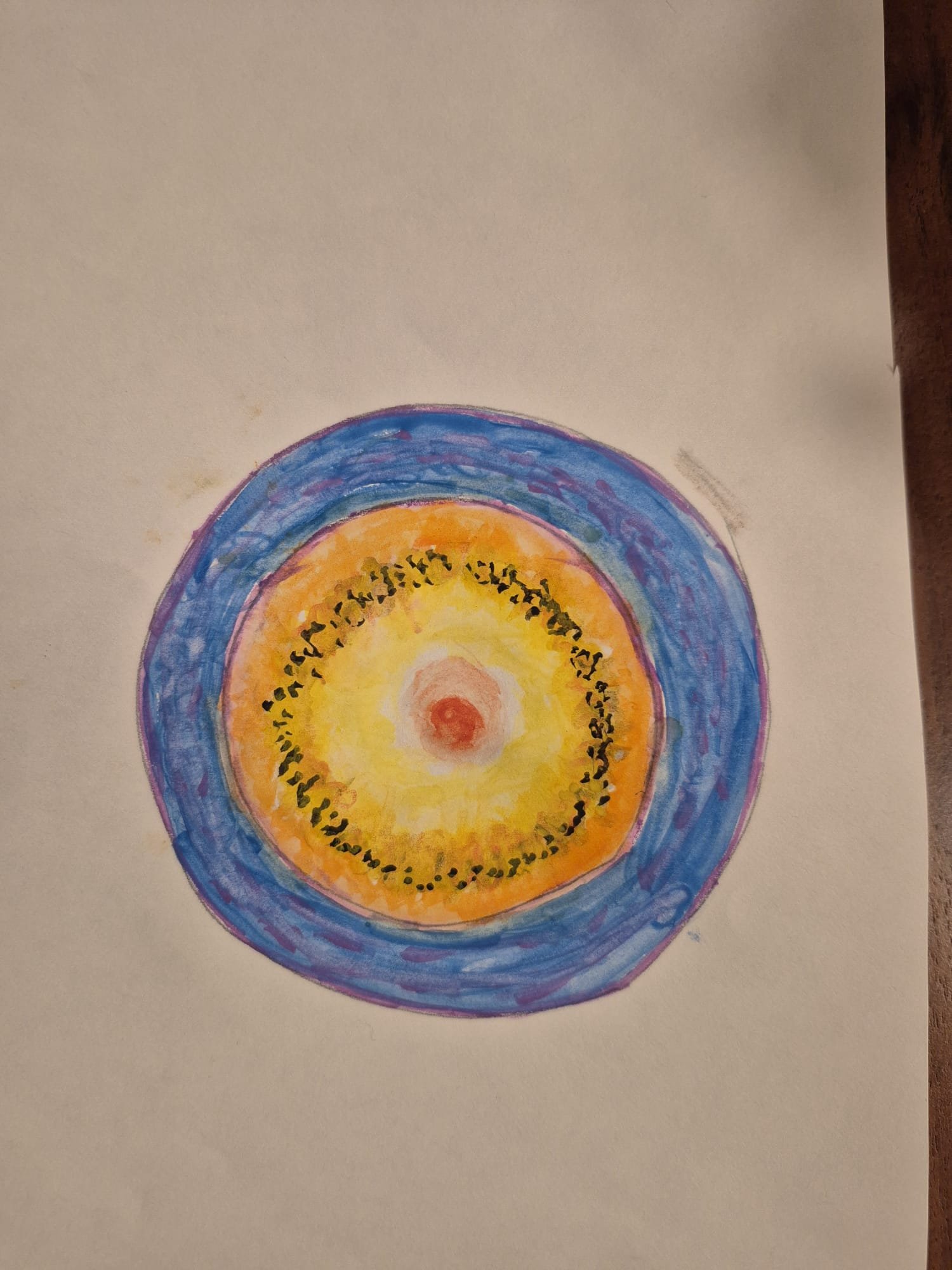

Women begin by grounding—often through a tree meditation. They feel the rootedness of their legs, the stretch of their inner branches, the vertical line of breath connecting earth and heaven. They breathe inside a circle of light, a Samech, sensing Divine support. They recall the candle-flame colors of the previous session—white, red, green, blue—and how each hue mirrors a spiritual force.

Teachings from the Bnei Yissaschar reveal that the sensory faculty of Kislev is Sheinah—sleep/dream-awareness—the state in which the soul receives new light. The Rebbe’s teachings on Yaakov’s dream deepen this: the place where “the head and the feet are equal,” where hierarchy dissolves, where Essence is revealed, where a single ladder connects worlds.

A right-hand/left-hand meditation supports emotional release: fear or pain held gently in the left hand, compassion in the right, drawing from the Divine Name of Chesed. Painting circles introduces darkness as integrator—how black softens, deepens, and reveals color, mirroring the inner process of healing.

None of this is psychological in the usual sense. It is shoresh-work—root work—spiritual and embodied, emerging through color, breath, Torah, and circle within the energetic architecture of Kislev.

And then the Breath Painting begins…

Circles within circles.

Darkness meeting light.

Color shifting with context.

Black deepening everything it touches.

The page slowly transforming into a mirror.

As women paint, something astonishing—and diagnostically profound—begins to occur. Their bodies shift before their words do: shoulders soften, breath deepens, eyes widen with a kind of ancient recognition. Long-held contractions uncoil. Pre-verbal layers stir. Memories surface not as stories but as sensation.

One woman described the moment her breath changed: “I didn’t even notice at first. It was like the circle rewired something in my lungs.” Another said, “A warmth rose behind my sternum. I think I’ve been holding that place since childhood.” Tears come not as breakdown but as release: “It wasn’t just crying—it was like something ancient was finally allowed to move.”

Color becomes its own language of healing. A participant painting black onto yellow panicked, then softened as it shifted into olive: “I watched my fear turn into something I could hold. It was like my life’s anxiety softened in front of me.” Self-compassion emerges without effort: “This was the first time in decades I felt kindness toward myself without trying.”

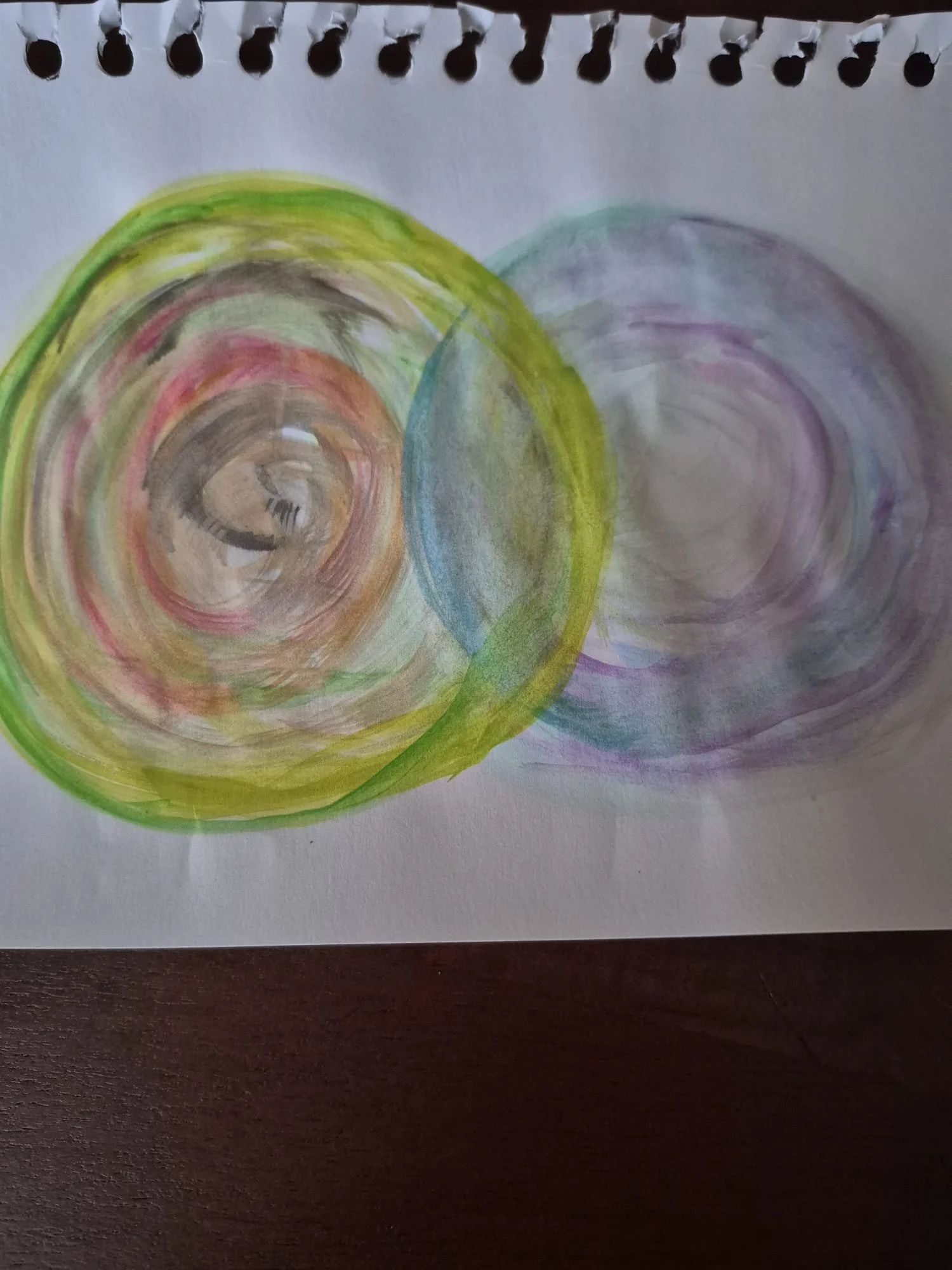

Intergenerational insight arises with equal clarity. “I always thought my mother was cold,” one woman said, “but tonight I saw her exhaustion. Something softened.” Others describe the power of overlap: “When the two circles touched, I felt forgiveness. The space between us changed.” Memories long buried rise safely: “A memory surfaced that I didn’t know I still carried—and it didn’t frighten me. I felt held.” Another whispered: “It felt like a womb inside me woke up.” And again and again: “I’ve been in survival mode for years. Tonight my body understood safety.”

These reflections reveal a landscape of transformation—breath resetting into parasympathetic calm, freeze responses thawing, pre-verbal memory surfacing and integrating, early attachment patterns repairing, intergenerational narratives reframing, compassion arising spontaneously, the nervous system regulating through rhythm and repetition, circles overlapping into yichud-consciousness, forgiveness emerging through contact rather than effort, and a profound reconnection to intrauterine safety.

Women consistently describe an inner experience that feels older than story—older even than language. It is the body remembering what the mind forgot.

This is not art.

This is awakening.

And from within that awakening, one theme rises with unmistakable clarity:

the maternal root.

The Maternal Root: Early Layers Reopening

The healing that arises in these workshops often reaches far deeper than participants expect. It is not simply emotional release, nor is it psychological insight in the conventional sense. It touches the earliest strata of the soul—the prenatal and pre-verbal layers shaped before language, before identity, before separation. These impressions, formed in the rechem (רֶחֶם — womb), are the original kelim through which a person learns safety, connection, belonging, and the felt-sense of self. In the language of the mekubalim, these layers correspond to the consciousness of Ima Ila’ah (אִמָּא עִילָאָה — Supernal Mother), the cosmic womb of bina, where all becoming is first held, softened, and given form.

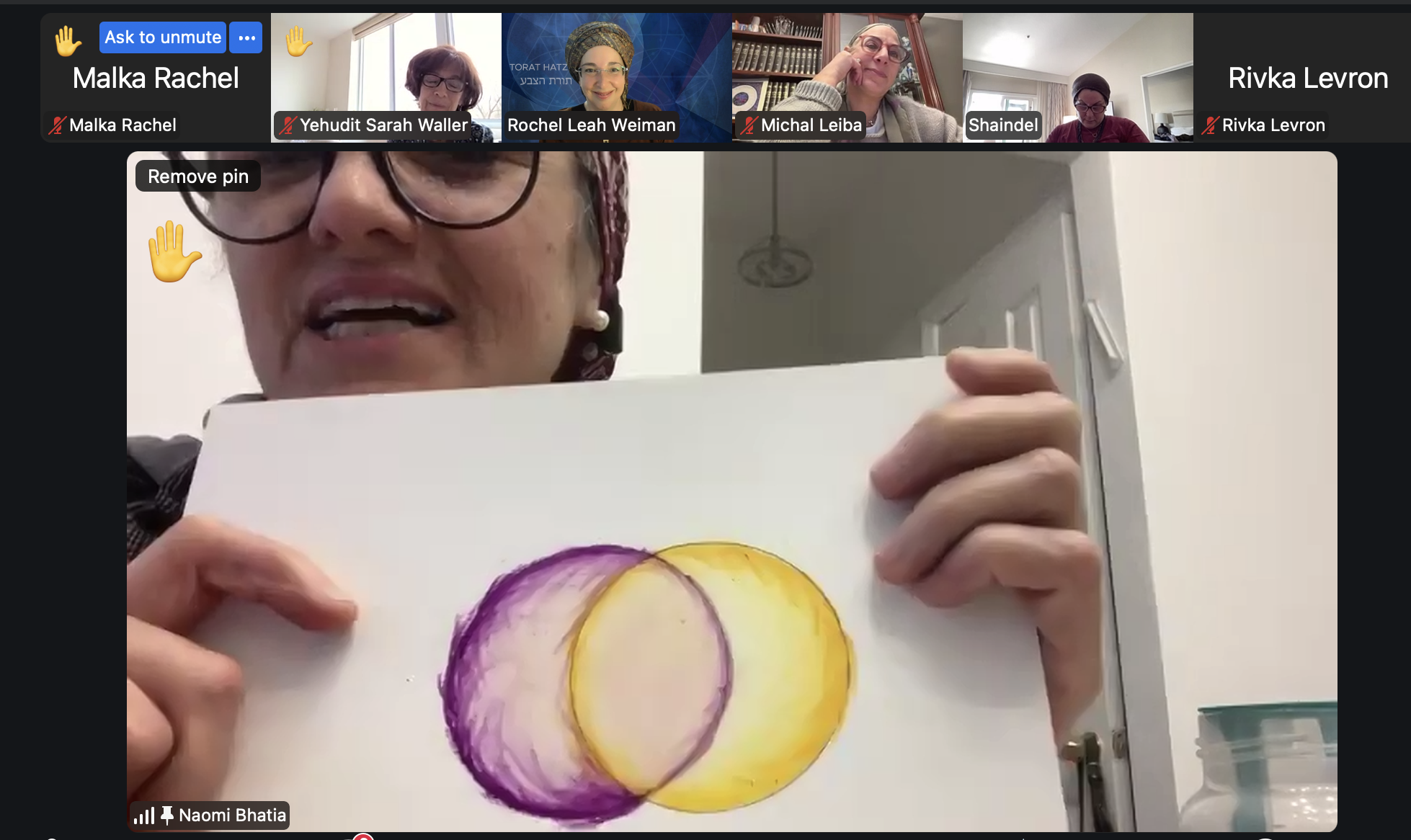

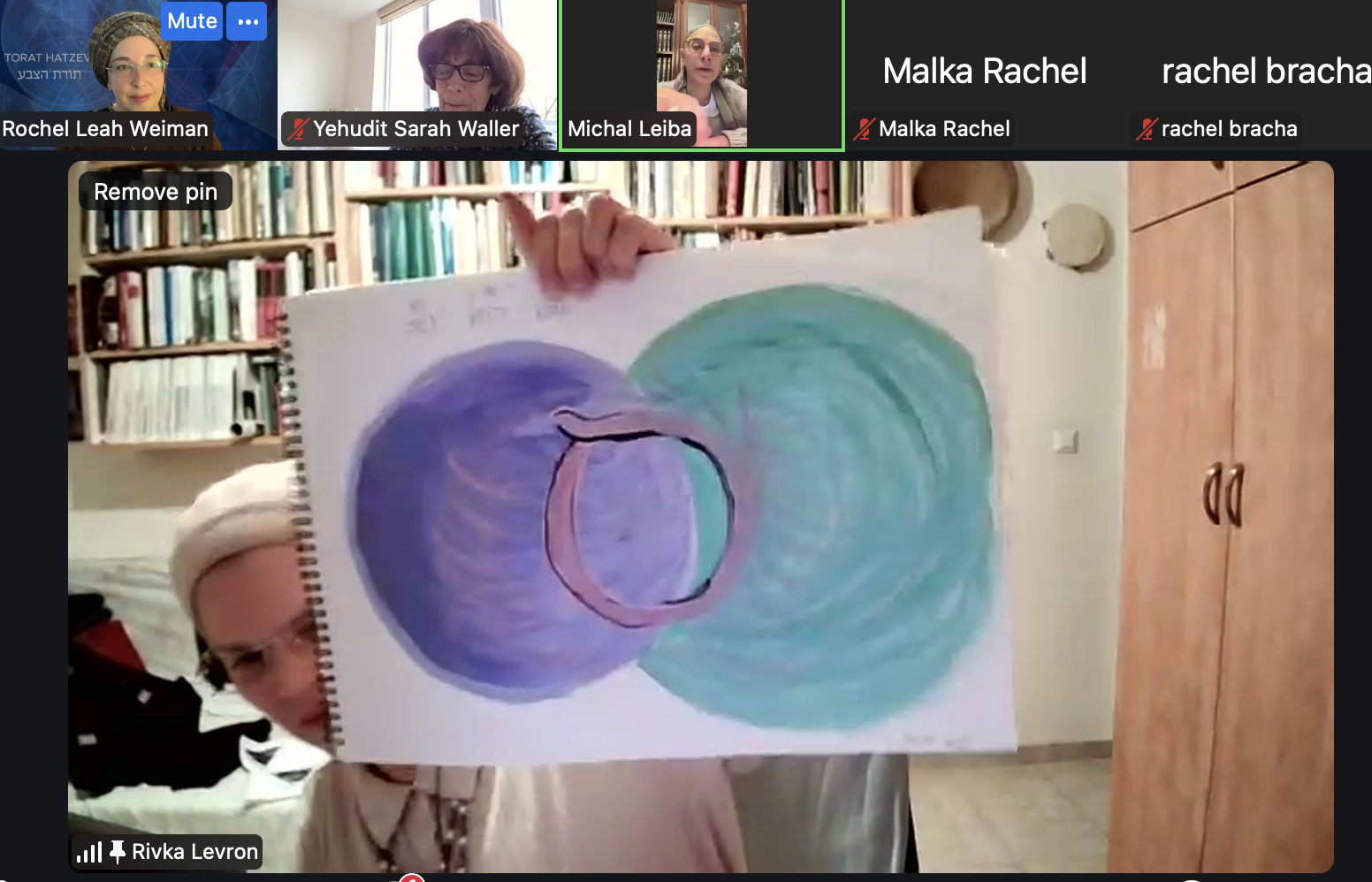

During circle-painting exercises, something profound often occurs. The body recognizes the circle before the mind does. As hands move in curved repetition, a memory awakens—older than story, older even than thought. Participants often describe a sensation of dropping into a The healing that unfolds in these workshops often reaches far deeper than participants anticipate. It does not remain on the surface of psychological insight, nor does it stay within the realm of emotion alone. Instead, it touches the prenatal and pre-verbal layers of the soul—those formed before language, before self-definition, before separation. These earliest impressions, shaped in the rechem (רֶחֶם — womb), carry an extraordinary imprint of how a person experiences safety, connection, belonging, and the felt-sense of “being held.”

In the writings of the Arizal, these primordial layers are associated with the consciousness of Ima Ila’ah (אִמָּא עִילָאָה — Supernal Mother), the womb-like domain of bina where all becoming is first softened, held, and given form.

Because the work touches such early strata, the atmosphere in the room naturally becomes soft, honoring, and oriented toward the good. The language centers on the light in each woman’s soul, and the quiet light in the souls of our mothers—the places of connection that existed even if later life obscured them. Participants are invited to rediscover the original tenderness that formed them, the early impressions of love, hope, and presence that predate any narrative of pain. The circle becomes a doorway back into this deeper truth, allowing women to reconnect with what shaped them long before memory, long before story.

During circle-painting, something profound begins to move. The body recognizes the circle before the mind does. As hands trace curved forms, many reconnect—viscerally—with the first circle they ever inhabited: the womb. Shoulders loosen. Breath deepens. The nervous system softens in ways usually seen only in the presence of great safety. Women speak of these shifts with reverent surprise:

• “When I painted the inner circle, something curled inside me—like a baby returning to the womb.”

• “I didn’t cry from pain. I cried from being held.”

• “This warmth in my chest… I think it’s the first place I ever learned connection.”

These are not metaphors; they are the unmistakable markers of pre-verbal memory stirring into light.

A woman tracing wide concentric circles paused and murmured,

“It felt like Rachel Imeinu’s arms were around me.”

Another added softly about Leah Imeinu,

“Not her sorrow—her strength. Her womb-light. Her hidden depth.”

Through these reflections, the Imahot—Rachel, Leah, Bilhah, Zilpah—shift from distant figures to living presences rising through the body’s remembering. Their tears, their endurance, their quiet radiance, their wordless faith become part of the healing field.

Women describe sensations that mirror early attachment repair:

• “My stomach softened. I didn’t know it could.”

• “It felt like someone was rocking me, but it was coming from inside.”

• “The circle felt like it was breathing with me.”

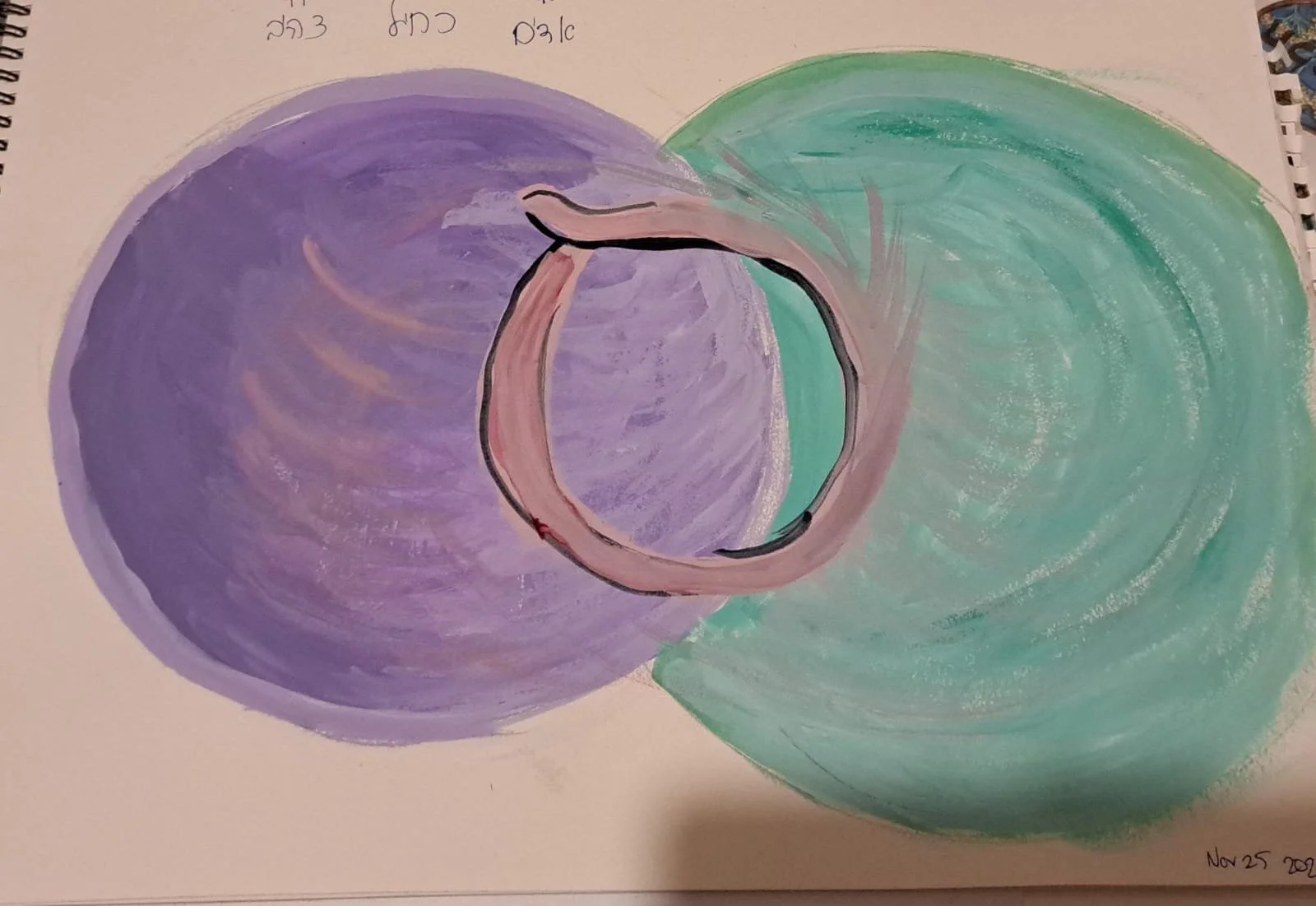

The overlap of circles—what Torat HaTzeva calls the Makom HaYichud (מקום הייחוד)—reveals even deeper layers. One participant layered two translucent circles and paused at the almond-shaped form emerging between them:

“This space… this is where healing happens. I felt forgiveness in my body before my mind understood.”

Another said,

“I always thought my mother was cold. Tonight I saw her exhaustion. Something eased.”

A gentle memory surfaced for someone else:

“I didn’t know I still carried that memory. It didn’t scare me. I felt held.”

Again and again, women articulate realizations that arise only from embodied truth:

• “I’ve been in survival mode for decades. Tonight my body tasted trust.”

• “My inner child didn’t just appear—she exhaled.”

These impressions reveal a landscape of transformation awakening beneath the surface:

breath settling into parasympathetic calm; freeze responses thawing; pre-verbal memory emerging safely; early attachment patterns reorganizing; intergenerational narratives softening; compassion rising naturally; the nervous system finding its natural rhythm through circular movement; overlapping circles awakening yichud-consciousness; forgiveness appearing without being summoned; a felt sense of intrauterine safety returning.

At a certain point, it becomes clear that this is not art making.

It is awakening.

It is teshuvat ha’guf—the body returning to its original design.

It is teshuvat ha’nefesh—the soul returning to its earliest softness.

It is teshuvat ha’yesod—the foundational repair upon which all other healing stands.

As these maternal layers soften and reorganize, something larger begins to reveal itself. The sense of healing no longer feels private or isolated. Women begin to feel themselves inside a wider story—one that touches lineage, memory, and the collective soul of Am Yisrael. The language in the room shifts from the personal to the ancestral, from the inner child to the shoresh neshama (soul-root), from the intimate circle of color to the expansive field of stones in Yaakov’s journey.

In this work, the same geometry that restores early maternal imprints—circle, overlap, yichud—emerges as the geometry of Jewish history itself. The womb-memory awakened through Samech becomes inseparable from the land-memory encoded in Torah. The individual narrative widens into the national; the inner circles become fields.

And so, near the end of each session, the attention naturally expands—not away from the self, but toward the larger pattern into which the self is woven. Women begin sensing that the same forces guiding their internal healing—color finding its vessel, breath finding its rhythm, pieces finding their place—mirror the ancient drama unfolding across generations.

Here is the expanded version you loved earlier—now polished, integrated, and written in full professional article prose.

This replaces the short line with the rich, nuanced segue you requested.

A Seamless Turning: From the Maternal Root to the Field

The movement is seamless, almost inevitable: from the soft, circular world of the maternal root into the wide, ancient landscape of the stones in the field. The transition does not feel like a shift of topic but like a widening of consciousness. What begins in the womb-like circle—the breath softening, the nervous system settling, the earliest layers of self reorganizing—naturally yearns for expression beyond the self. Just as in the structure of the soul described in Eitz Chaim, where “akevei Leah nichnasim b’Rosh Rachel”—the heels of Leah descend into the head of Rachel—so too the hidden, preverbal world (Leah-consciousness) flows into the relational, articulated world (Rachel-consciousness) at the point of Tiferet in Yaakov.

In the workshops, this descent can be felt somatically. What was once only sensation becomes insight. What was preverbal becomes relational. What was internal becomes expressive. The circle widens into a path. The personal becomes inseparable from the collective. The individual story begins to recognize itself within the larger story of Am Yisrael.

Women often describe this turning with awe—how, after the inner softening, their awareness suddenly shifts outward without losing intimacy. The breath that just moments ago held an inner child now begins to feel braided into something ancestral. Color that once touched only private memory now begins to reflect the palette of generations. The geometry of the circle begins to open into the geometry of the land.

This widening is not forced. It is not conceptual. It arises with the quiet logic of the soul itself.

The women sense—almost before it is spoken—that the same forces guiding their inner healing

color finding its vessel,

breath finding its rhythm,

pieces finding their place,

mirror the ancient drama that unfolds in the parshiyot of Yaakov.

Personal coherence reveals itself as a microcosm of national coherence.

The awakened maternal root begins to feel its echo in the scattered stones of Yaakov’s field.

The circle remembers that it is also a path.

The womb remembers that it is also a land.

And so the attention turns, naturally and inevitably,

from the maternal root

to the stones in the field.

Stones in the Field: Personal and National Geulah

n Torat HaTzeva, the inner work inevitably mirrors the national, because the Jewish soul contains within it the entire story of the nation. What happens in the individual psyche echoes what has unfolded across generations. The personal palette and the collective palette share the same colors. The same geometry that heals early maternal impressions—circle, overlap, yichud—also underlies the story of Am Yisrael itself.

During the workshops, teachings arise almost organically from the parsha. As women move between breath, color, movement, and circle, we find ourselves returning again and again to the scenes of Yaakov’s journey:

Yaakov leaving home; avanim (אבנים)—stones—scattered across a field; vulnerability; chalom (חלום)—dreams; ladders between worlds; malachim (מלאכים) ascending and descending. These images resonate naturally with Torat HaTzeva’s core language of or (אוֹר, light), kli (כְּלִי, vessel), tzeva (צֶבַע, color), and relational geometry.

Why stones?

Because life often feels like that field—pieces everywhere, disconnected, random, resistant to meaning. Relationships scattered. Emotions lying under the surface like cold, unmoving stones. Personal and collective history marked by rupture and shattering. In Rav Kook’s language, this is the pain of hitpardut (התפרדות—fragmentation), the felt distance between essence and expression, between tree and fruit.

Yet Yaakov shows us the earliest blueprint of geulah (גאולה, redemption):

He gathers the stones.

He arranges them.

He makes from them a foundation.

This physical gathering mirrors what happens internally through Torat HaTzeva. In color language, scattered stones resemble unintegrated tzirufim (צירופים)—combinations waiting to be harmonized. The emotional scattering reflects orot (אורות, lights) in search of keilim (כֵּלִים, vessels). Yaakov’s act becomes the spiritual architecture of healing: bringing what is scattered into relationship.

Later, Rabbi Akiva stands before the ruins of the Beit HaMikdash and laughs—not out of denial, but because he can perceive pri (פְּרִי, fruit) hidden within the broken tree. He can gather from destruction the seeds of redemption. In Torat HaTzeva terms, he sees the color inside the darkness, the new tone emerging from the overlap, the ohr ha’ganuz (אוֹר הַגָּנוּז)—the hidden light—inside the fracture. Rav Kook writes that the tzaddik and the generation of teshuva “return on the essence of the break itself,” transforming pgam (פגם—damage) into song, fracture into new melody.

This is the feminine way.

Not denying the shattering.

Not rushing the rebuilding.

But gathering the pieces.

Softly. Quietly. With faith.

We live in a generation of immense light—and immense shattering.

A single siren can fragment a soul.

A single loss can send pieces in every direction.

Families, communities, and inner worlds are left holding the debris.

Yet hidden within this scattering is a profound spiritual calling:

geulah-consciousness—the art of gathering sparks, gathering stones, gathering the pieces of self and nation into a new wholeness.

Jewish tradition names two intertwined soul-forces that guide this process:

• Nishmat Moshe (נשמת משה) — the soul-root of order, structure, halachic boundary, the eitz (עֵץ), the tree.

• Nishmat Mashiach (נשמת משיח) — the soul-root that emerges from rupture (Lot, Tamar) and transforms darkness into diamond, sin into merit, shattering into sweetness—the pri (פְּרִי), the fruit.

In Torat HaTzeva, these two energies meet. The structured practice of breath, circle, and color provides the tree; the emotional honesty and spiritual unveiling that arise through the process become the fruit. Together, they complete each other:

Tree and fruit. Process and revelation. Color in the vessel. Light finding its home. Stones scattered and stones gathered.

This is the work of Torat HaTzeva in our generation: teaching women to gather what has been dispersed—internally, interpersonally, and collectively—until the scattered stones reveal themselves as the foundation of something entirely new. In Rav Kook’s terms, this is teshuvat ha’olam—the world itself returning to its hidden wholeness, one inner gathering at a time.

The War and the Light in the Field

Our generation carries a profound and unmistakable weight. Parents are still holding the unprocessed tension of decades. Soldiers carry both the light and the trauma of impossible days. Families navigate layers of heartbreak from war and loss. Children are born into a world already vibrating with collective anxiety.

This is the reality of ikvesa d’Meshicha (עִקְבְתָּא דִמשִׁיחָא)—the footsteps of Mashiach—an era described in our tradition as one in which vessels crack before the light can expand. The ohr gadol (אוֹר גָּדוֹל), the great and overwhelming light of redemption, often arrives with such intensity that it shatters the structures meant to contain it. The result is a landscape that feels fragmented: stones scattered across every field of our lives.

And yet, the shattering is not the end of the story. In many ways, it is the beginning of the gathering.

Our chachamim teach this through the image of Rabbi Akiva, who stood before the ruins of the Beit HaMikdash and saw within the devastation the seeds of future joy. He recognized that destruction and redemption are not opposites, but stages in a single unfolding process. Rav Kook echoes this when he writes that “the great light that seems to break us is the very light that will one day heal us,” for within every break lies a deeper capacity for wholeness.

Today, a parallel awakening is visible among women. They are learning how to stand inside their own scattered fields—inside the fragmentation of family history, emotion, trauma, and memory—and begin to gather. Not all at once, and not through force, but breath by breath, color by color, circle by circle. Through the embodied language of Torat HaTzeva, they are discovering the quiet capacity to bring pieces back into relationship.

This, too, is a form of Mashiach-consciousness: the ability to recognize light inside the fracture, to locate meaning within the breaking, and to assemble the scattered stones of a life into a foundation from which something new can grow. It is geulah not as abstraction, but as lived practice—through hands, breath, pigment, and prayer.

Every Circle is a Womb: Samech as Healing Geometry

As women begin to gather the scattered pieces of their lives, a deeper pattern starts to emerge. The act of gathering—whether emotional, spiritual, or generational—naturally leads them back to one of the central symbols of Torat HaTzeva: the Samech (ס). In many ways, the movement from fragmentation to wholeness is the movement from a field of scattered stones back into a circle. And this circle is not simply a shape; it is a spiritual structure.

Samech is not a letter.

It is a worldview.

A perfect circle with no break, no beginning, and no end, it represents a geometry of trust, containment, and gestation. In Torat HaTzeva, Kislev draws the soul directly into this Samech-consciousness. It invites an experience of the circle as womb, the womb as universe, and the universe as circle—each one a vessel for holding and transforming light.

In the workshops, women often describe a sense of being physically and emotionally held when they breathe into the circular form. This sensation is not metaphorical. It has neurological, somatic, and spiritual reality. Many speak of feeling “wrapped,” “carried,” or “suspended,” as though embraced by something far beyond human capacity. Quite literally, the body begins to remember what it once knew in the rechem (רֶחֶם—womb): that existence itself began inside a circle of unconditional holding.

Here the Zohar offers a crucial teaching:

“Kol ohr nigleh lefi ha’kli” — כׇּל אוֹר נִגְלֶה לְפִי הַכְּלִי

“All light is revealed according to its vessel.”

The circle is the vessel.

Samech is the vessel.

The womb is the vessel.

And eventually, the body becomes the vessel.

When these vessels—womb, circle, soul—align, the earliest layers of experience reopen gently. Compassion rises. Memory softens. What was sealed begins to move. Darkness becomes approachable in Kislev precisely because the container is strong enough to hold it.

This is why color becomes deeper when black is added.

This is why the soul reveals hidden light when it feels held.

And this is why healing in these workshops often unfolds with surprising immediacy.

Not because of the art alone.

Not because of the meditation alone.

Not because of the learning alone.

But because of their fusion—a fusion that returns the soul to its original holding environment, to its womb-consciousness, where light was known before it fractured into color and experience.

In the language of Torat HaTzeva, this is a return to Ohr Ein Sof (אוֹר אֵין־סוֹף), the Infinite Light, to the primal unity in which all colors existed as one—the collective radiance of Ohr Pashut (אוֹר פָּשׁוּט), the simple, undifferentiated light. It is, in Rav Kook’s terms, a taste of the future world breaking into the present—a geulah that begins not in history books, but in the breath, in the body, in the circle, here and now.

CONCLUSION · THE EMERGING GEULAH OF COLOR, BREATH & CIRCLE

As the work of Torat HaTzeva unfolds—circle by circle, breath by breath, stone by stone—a larger pattern begins to shimmer beneath the surface. The personal awakens the ancestral. The maternal awakens the national. The individual awakening becomes inseparable from the awakening of the generation.

What begins as a tremor in a woman’s chest becomes a tremor in the field of Am Yisrael.

And it becomes unmistakably clear:

we are living within the opening movements of geulah-consciousness.

Rav Kook teaches that redemption begins subtly, internally—“הגאולה הפנימית של הנשמה”—the inner geulah of the soul—and only afterward reveals itself outwardly in the world. He writes that when a generation begins to recover its lost sweetness, its original light, its inner unity, the footsteps of geulah come near. This is the work we witness in these circles of color and breath: a generation recovering its early sweetness, its early safety, its early song.

And this is precisely what the women themselves are describing, often without knowing the full spiritual resonance of their words.

Emerging Geulah Consciousness

A new consciousness begins to rise—a geulah that does not erupt violently but emerges from within, through softness, color, breath, memory, and song. Women become healers, artists of the soul, quiet sparks of Miriam reawakening beneath the surface of post-war exhaustion and longing.

There is a sense of stepping toward a collective future the way our ancestors once stepped toward the sea—tambourines still tentative in hand, but emunah intact, with unsung songs and unexpressed longing rising from the depths of the heart.